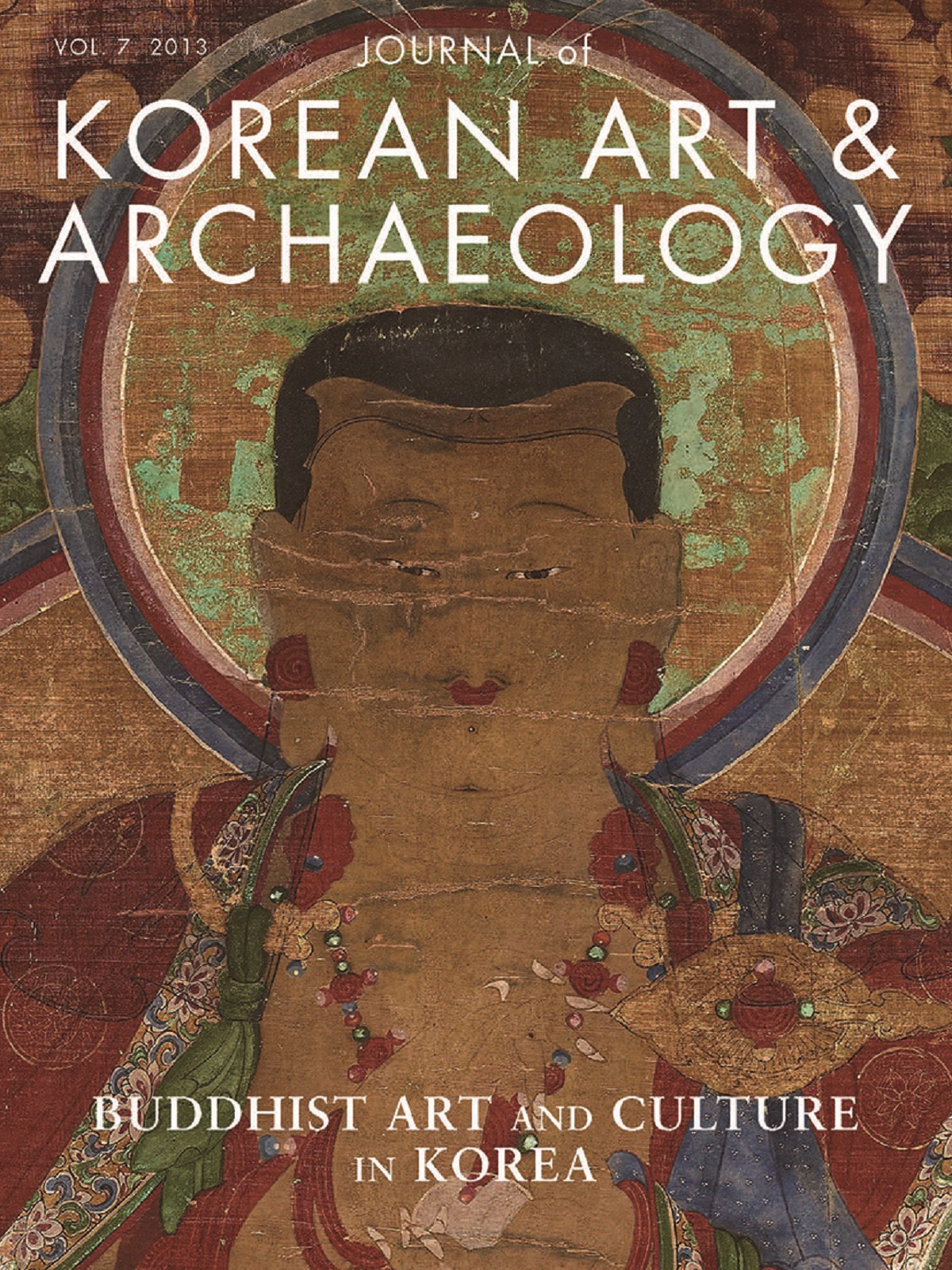

Journal of Korean Art & Archaeology 2013, Vol.7 pp.40-59

Copyright & License

During the mid-Goryeo Dynasty (1046-1270), notable Buddhist sculptures emerged, influenced by Chinese Song art. Goryeo sculptures displayed bodhisattvas in "royal ease" posture, influenced by Chinese regions, especially southern China and Song-era motifs. Styles like relaxed postures, decorative elements, and new materials such as gamtang and rock-crystal eyes were evident. These influences arrived through maritime routes and were integrated into the unique Goryeo aesthetic, showcasing artistic exchange between China and Korea.

Preface

The middle period of the Goryeo Dynasty extends from the reign of King Munjong (文宗, r. 1046-1083), when Goryeo shared a close relationship with the Liao (907-1125) and Song (960-1279) Dynasties of China, through the Goryeo Military Regime (1170-1270). The Buddhist sculpture of this 200-year period is especially notable, due to the emergence of new forms and styles, such as sculptures showing bodhisattvas in the relaxed posture of royal ease; increased popularity of wooden sculptures and the dry lacquer technique; the insertion of rock crystal for the eyes; and the use of a pliable substance called gamtang to depict hair and jewels. Some of these new characteristics represent the influence of Song Dynasty. Diplomatic relations between Goryeo and Song began during the reign of King Gwangjong (光宗, r. 949-975) and continued through 1030, when Goryeo sent a delegation of 293 envoys to Song. After that, relations seem to have been temporarily discontinued, as there are no known records of any exchanges until the sixth month of 1072 (26th year of King Munjong), when Song sent medical officials, a Royal Rescript, and official gifts to Goryeo, as reported in Goryeosa(高麗史, History of Goryeo). It would seem that Goryeo and Song began full diplomatic relations at this time, as accounts of further cultural exchanges between Goryeo and Northern Song (960-1127) can be found in several other historical documents, including Goryeosa and Xuanhe fengshi Gaoli tujing (宣和奉使高麗圖經, Illustrated Record of the Chinese Embassy to the Goryeo Court in the Xuanhe Era). Various records by monks also provide evidence of relations between Goryeo and Song, including the travel records of Monk Controller Uicheon (義天, 1055-1101) describing his travels to Bianjing (capital of Northern Song, present-day Kaifeng, in Henan province) and Mingzhou (present-day Ningbo, in Zhejiang province) in 1085.

This paper examines characteristics of Buddhist sculpture from the mid-Goryeo period to ascertain the influence of the arts of the Song Dynasty. In addition, the route by which iconographic characteristics may have been imported from Song will be theorized through an examination of excavation sites, maritime routes, and beliefs in Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva.

Influence of Song Buddhist Sculpture during the Mid-Goryeo Period

Compared to the early Goryeo period (918-c. 1070), there are relatively few extant Buddhist sculptures from the mid-Goryeo period (c. 1070 to 1270); those with engraved inscriptions are especially scarce. Two of the more notable characteristics of these rare sculptures are the relaxed postures of the bodhisattvas and the decorative techniques used to render hair, jewels, and crowns.

Relaxed Bodhisattva: Posture of Royal Ease

The “posture of royal ease” refers to bodhisattvas in a stable, seated position, with the right arm extended out to rest casually on the upraised right knee, the left leg bent and tucked in against the body, and the vertical left arm firmly planted back on the pedestal. Three mid-Goryeo statues of bodhisattvas seated in this stance are currently known: a bronze seated bodhisattva from Goseongsa Temple in Gangjin, South Jeolla Province (Fig. 1); a gilt bronze seated bodhisattva from Daeheungsa Temple in Haenam, South Jeolla Province (Fig. 2); and a gilt bronze seated bodhisattva in the collection of the National Museum of Korea (Fig. 3). The same pose can also be seen in a bronze seated bodhisattva from Seocheon, South Chungcheong Province (Fig. 4), which is known only from a photograph in Joseon Gojeok dobo (朝鮮古蹟圖譜, Album of Ancient Sites and Monuments of Korea), a catalogue series published by the Japanese Government-General of Korea (1910-1945). Thus, there are currently four known examples of bodhisattva sculptures from the mid-Goryeo period depicting the bodhisattva in the posture of royal ease.

Fig. 1. Seated bronze bodhisattva from Goseongsa Temple in Gangjin, South Jeolla Province. Late twelfth - early thirteenth century. Height: 51.0 cm. (Author’s photograph).

Fig. 2. Seated gilt bronze bodhisattva from Daeheungsa Temple in Haenam, South Jeolla Province. Late twelfth - early thirteenth century. Height: 49.3 cm. (Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage).

Fig. 4. Seated bronze bodhisattva from Seocheon, South Chungcheong Province. Eleventh - twelfth century. Height: 15.0 cm. Originally printed in Joseon Gojeok dobo (朝鮮古蹟圖譜) and reprinted in Study of Late Goryeo Buddhist Sculpture (고려후기 불교조각 연구) by Jeong Eunwoo. (PhD dissertation, Hongik University, 2001, Fig. 3).

Popular from the Goryeo into the early Joseon period, the royal ease posture is typically reserved for the Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara. In China, the earliest known image of a figure seated in this pose is a bodhisattva incised on a mirror dated 985 (currently housed in Seiryoji Temple, Kyoto, Fig. 5). This posture seems to be almost exclusively associated with the southern regions of China, and is rarely seen among Liao sculptures from the northern regions of China. In fact, there is only one known sculpture of a bodhisattva with this pose from the Liao Dynasty, along with a few from the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234), also in China’s northern regions, some of which are found in the Shihongsi Caves in Yanan, Shaanxi Province. The prevalence of this posture in sculptures from China’s southern regions is likely due to the area’s association with the Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara, who was believed to reside on Mt. Potalaka, a spiritual mountain believed to be located in the seas south of India. Images of this bodhisattva in the posture of royal ease continued to develop and spread into Korea and Japan. For example, in Japan, volume 22 of Besson zakki (別尊雜記, Assorted Notes on Individual Divinities), a work from the twelfth century, includes a painting of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva in this pose (Fig. 6), said to have been made by an artist from Quanzhou, China. Another Avalokiteshvara with the same pose can be seen in the Japanese painting titled Kegon kaie zenchishiki mandara (華嚴海會善知識曼多羅, The Spiritual Mentors of the Avatamsaka Ocean Assembly) from the thirteenth century. Images of bodhisattvas in this posture also seem to have been disseminated to Korea in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, likely through maritime routes from Quanzhou and Mingzhou. Today, there are approximately ten known Goryeo statues of bodhisattvas seated in the royal ease posture, as well as roughly ten mirrors with incised images of bodhisattvas assuming the same pose.

Fig. 5. Bodhisattva incised on a mirror. 985. Seiryoji Temple, Kyoto. Ningbo, the Holy Place (聖地寧波). (Nara: Nara National Museum, 2009, p. 24).

Fig. 6. Avalokiteshvara bodhisattva from the 22nd volume of Assorted Notes on Individual Divinities (別尊雜記). Twelfth century. Ningbo, the Holy Place (聖 地寧波). (Nara: Nara National Museum, 2009, Fig. 94).

Based on such evidence, the motif of bodhisattvas in the royal ease posture likely came to Goryeo during the Northern Song period. There are at least two early examples of statues in this posture from the Goryeo Dynasty. The first is a seated bronze bodhisattva from Seocheon, South Chungcheong Province (Fig. 4), which is known only from a photograph in Joseon Gojeok dobo (朝鮮古蹟圖譜, Album of Ancient Sites and Monuments of Korea). Based on the photo, the sculpture’s lean body and face indicate that it was probably produced in eleventh or twelfth century. The second example is the seated gilt bronze bodhisattva in the collection of the National Museum of Korea (Fig. 3) which has a lean body, slender waist, and a number of decorative details, including a tall leaf-shaped crown, Buddhist prayer beads in the right hand, bracelets on the wrists, and a robe with a double-pointed lower edge, like a swallow’s tail. The features of this sculpture are visually similar to those of a standing gilt bronze bodhisattva in the collection of Dongguk University Museum, as well as to a bodhisattva from a gilt bronze Vairocana triad at Yeongtapsa Temple, both of which are believed to have been produced during tenth or eleventh century. Based on those features, both the Seochon bodhisattva in Figure 4 and the seated gilt bronze bodhisattva in Figure 3 probably were produced around the same time, in the eleventh or twelfth century (Jeong Eunwoo 2006).

The bronze seated bodhisattva from Goseongsa Temple in Gangjin (Fig. 1) and the gilt bronze seated bodhisattva from Daeheungsa Temple in Haenam (Fig. 2), both from South Jeolla Province, resemble each other but differ from the two bodhisattvas mentioned above. The Gangjin bodhisattva is 51.0 centimeters tall, making it the largest known Goryeo example of a bodhisattva seated in the posture of royal ease. Its head is relatively large in comparison to its body and it displays a very natural facial expression. The body is somewhat plump, with a voluminous chest and round belly. Around its neck is a simple yet elegant beaded necklace, highlighted by a small f lower pendant that appears in the center of the chest. At 49.3 centimeters, the gilt bronze seated bodhisattva from Haenam is almost as tall as the one from Gangjin. They are also very similar in terms of the overall form and decorative details. For instance, both figures have their hair arrayed in a similar fashion, with braids that loop around the ears and hang down across the shoulders. A number of the other details are also quite similar, including the voluminous chest, round belly, nipples, beaded necklace, the creases in the robe around the right knee, the big toes (either raised or lowered), and the way the left arm is planted gently on a fold from the robe.

Some of these features—such as the necklace, hair, voluminous body, round belly, and loose clothing—can be found in other sculptures of bodhisattvas from the Song Dynasty. For example, the style of the necklace resembles that of the Samantabhadra Bodhisattva from the Hall of Sakyamuni in Qingliansi Temple (靑蓮寺) in Jincheng, Shanxi Province, which was produced in the Northern Song period (Fig. 7). A similar necklace can also be seen on the wooden seated bodhisattva currently housed in Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Cultural History in Japan (Nara National Museum 2009, 93), which was produced during the Northern Song period. The long braids of hair draped over the shoulders are characteristic of Buddhist art of the Southern Song period (1127-1279), such as the wooden seated bodhisattva from Sennyuji Temple in Kyoto, Japan (Fig. 8). Notably, the bodhisattva in Figure 4 also features a voluminous body and a somewhat stubby nose, much like the bodhisattva from Goseongsa Temple (Fig. 1a). The round belly and loose clothing can also be seen in a pair of Song-Dynasty sculptures now housed in Japan: the wooden bodhisattva from Seiunji Temple, Kanagawa (Fig. 9) and the wooden seated bodhisattva from Hoonji Temple, Hyogo (Fig. 10). Based on these examples, the loose clothing, voluminous chest, and round belly have been categorized as the features of the late Northern Song and Southern Song periods.

Fig. 7. Samantabhadra Bodhisattva. Northern Song. Hall of Sakyamuni of Qingliansi Temple in Jincheng, Shanxi Province. Buddhist Colored Statues from Shanxi (山西佛敎彩塑). (Beijing: Chinese Buddhism Association, 1991, Fig. 77).

Fig. 8. Wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Sennyuji Temple, Kyoto, Japan. Southern Song Dynasty. Height: 113.8 cm. (Author’s photograph).

Fig. 9. Wooden bodhisattva from Seiunji Temple, Kanagawa. Ningbo, the Holy Place (聖地寧波). (Nara: Nara National Museum, 2009, Fig. 91).

Fig. 10. Wooden bodhisattva from Hoonji Temple, Hyogo. Ningbo, the Holy Place (聖地寧波). (Nara: Nara National Museum, 2009, Fig. 92).

As previously mentioned, the two bodhisattvas from Seocheon and the National Museum of Korea (Figs. 3 and 4) are believed to have been produced in the eleventh or twelfth century. The other two bodhisattvas, from Goseongsa Temple in Gangjin and Daeheungsa Temple in Haenam (Figs. 1 and 2), are thought to date from the late twelfth or early thirteenth century. Goseongsa Temple is a branch temple of Daeheungsa Temple, and the two are located relatively close to one another. In Beomugo (梵宇攷, On Buddhist Temples, Past and Present), published in 1799, Goseongsa Temple is recorded as “Goseongam Temple.” In addition, a stele on Mt. Cheonbul provides further details about Hwaeomsa Temple (千佛山華嚴寺事蹟碑), stating that a monk named Yo Se (了世, 1163-1245) built Goseongsa Temple at the same time that he rebuilt Baengnyeonsa Temple, from 1211 through 1216. Given that the sculptures would have been enshrined immediately after the temples were constructed, these records provide us with approximate dates for the statues.

Decorative Techniques

The three most representative twelfth- and thirteenth-century Goryeo sculptures of the Buddha are a wooden seated Buddha in Gaeunsa Temple, Seoul (produced before 1274, originally located in Chukbongsa Temple, Asan, South Chungcheong Province); a wooden seated Amitabha Buddha in Gaesimsa Temple, Seosan, South Chungcheong Province (before 1280); and a dry-lacquer seated Buddha in Simhyangsa Temple, Naju, North Jeolla Province (Jeong Eunwoo 2008; Choe Seongeun 2008). The approximate date of the sculpture from Chukbongsa Temple is known from a written prayer installed inside the statue, which records that the statue was repaired in 1274. Similarly, a handwritten ink document found inside the statue from Gaesimsa Temple states that it was repaired in 1280. All three of these statues display features that are characteristic of sculptures of the Buddha from the Southern Song period (Mun Myeongdae 1996; Choe Seongeun 2008).

The two most representative twelfth- and thirteenth-century Goryeo sculptures of bodhisattvas are a wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bongjeongsa Temple (1199, 104.0 centimeters in height, Fig. 11) and one from Bogwangsa Temple (c. thirteenth century, 113.6 centimeters in height, Fig. 12), both in Andong, North Gyeongsang Province. Both of these sculptures display the formal stylistic features associated with the Southern Song period, such as a bold, dignified facial expression, an outer robe that covers the shoulders, and billowing sleeves that drape across the knees. The bodhisattva sculpture from Bongjeongsa Temple is made from pine wood; a plaque at the temple states that it was made in 1199. The bodhisattva statue from Bogwangsa Temple is made from juniper wood and is believed to date to the thirteenth century, based on devotional and dedicatory objects found inside the sculpture (Son Yeongmun 2009).

Fig. 11. Wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bongjeongsa Temple, Andong, North Gyeongsang Province. 1199. (Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage).

Fig. 12. Wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bogwangsa Temple in Andong, North Gyeongsang Province. (Author’s photograph).

Both of these bodhisattva sculptures feature several notable technical features that reflect the influence of the arts of the Song Dynasty. First, although both sculptures are made from wood, the hair and jewels of each are formed of a material called gamtang (Fig. 12a). The exact ingredients of gamtang are unknown, but based on the yellow residue that remains where the gamtang was applied (Fig. 12b), it is believed to be consist of a mixture of wax, pine resin, and other ingredients. Before gamtang was applied, the surface of a wooden statue was coated with lacquer and then covered with pieces of hemp cloth. Layers or pieces of gamtang were then attached to simulate hair or jewels. For example, strips of gamtang were laid across the head and then incised with fine lines to represent strands of hair (Fig. 12c). The jewels were molded separately from gamtang and appliqued; some of them have become detached and disappeared over the years. The strips of cloth used to affix the gamtang can be clearly seen in X-ray photos (Fig. 12d). X-ray photography has confirmed that gamtang was also used to form the hair of other sculptures made about the same time, including a dry-lacquer seated bodhisattva from Cheongnyangsa Temple (Fig. 13), a wooden seated Buddha from Suguksa Temple (Fig. 13a), and a late-Goryeo bodhisattva in Japan’s Okura Collection (Fig. 13b).

Fig. 12a. Gamtang of wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bogwangsa Temple. (Author’s photograph).

Fig. 12b. Head of wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bogwangsa Temple. (Author’s photograph).

Fig. 12c. Back of wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bogwangsa Temple. (Author’s photograph).

Fig. 12d. X-ray photos of wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bogwangsa Temple, showing gamtang technique. (Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage).

Figs. 13, 13a, and 13b. X-ray photos of statues from Cheongnyangsa Temple, Suguksa Temple, and Okura Collection (respectively), showing gamtang technique. (Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage).

A second important decorative feature of both statues is the insertion of rock crystal to represent the eyes, a technique that has also been found among other dry-lacquered and wooden Buddhist statues from the mid-Goryeo period (Figs. 14, 14a, and 14b). The earliest known example of a Goryeo sculpture with rock-crystal eyes is a wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bongjeongsa Temple. Table 1 shows a total of ten such sculptures, dating from the mid-Goryeo to the early Joseon period, and mostly located in North Gyeongsang Province and South Jeolla Province.

Fig. 14. Crystal eye insertion shown from the inside of the head of the statue from Cheongnyangsa Temple. (Cheongnyangsa Temple).

Figs. 14a and 14b. X-ray photos of statues from Suguksa Temple and Okura Collection (respectively) showing how the crystal eyes were inserted. (Suguksa Temple and gift from a Japanese scholar).

| Name | Date | Location | Height (cm) | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bongjeongsa Temple | 1199 | Andong, North Gyeongsang Province | 104.0 | Treasure #1620 |

| 2 | Dry-lacquer seated bodhisattva from Cheongnyangsa Temple | Goryeo | Bonghwa, North Gyeongsang Province | 90.0 | |

| 3 | Dry-lacquer seated Bhaisajyaguru from Cheongnyangsa Temple | Goryeo | Bonghwa, North Gyeongsang Province | 92.5 | |

| 4 | Wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bogwangsa Temple | Goryeo | Andong, North Gyeongsang Province | 113.6 | Treasure #1571 |

| 5 | Wooden dry-lacquer seated Buddha from Simhyangsa Temple | Goryeo | Naju, South Jeolla Province | 136.0 | Treasure #544 |

| 6 | Wooden seated Buddha from Suguksa Temple | Goryeo | Seoul | 104.0 | Treasure #1580 |

| 7 | Dry-lacquer seated Amitabha Buddha from Seonguksa Temple | Goryeo | Namwon, South Jeolla Province | 132.0 | Treasure #517 |

| 8 | Dry-lacquer seated Vairocana Buddha from Bulhoesa Temple | Goryeo | Naju, South Jeolla Province | 128.0 | Treasure #545 |

| 9 | Dry-lacquer seated Buddha from Jungnimsa Temple | Joseon | Naju, South Jeolla Province | 116.0 | |

| 10 | Dry-lacquer seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Naksansa Temple | Joseon | Yangyang, Gangwon Province | 143.0 | Treasure #362 |

| 11 | Wooden seated Buddha from Gaesimsa Temple | Goryeo (before 1280) | Haemi, South Chungcheong Province | 120.5 |

Table 1. Statues with crystal eyes.

Notably, the pieces of rock crystal were not simply attached to the exterior surfaces of the statues. Rather, the hollow statues were made with empty eye sockets, into which the crystals were inserted via the interior. After the holes for the eye sockets were made and the outer surfaces smoothed down, the rock-crystal pieces were inserted into the interior and affixed into the sockets with a mixture of pine resin, crude lacquer, or wax. The crystals were often painted to represent the eye’s iris and pupil. X-ray photography of the dry-lacquer seated bodhisattva from Cheongnyangsa Temple shows that its rock-crystal eyes were held in place with a lacquered hemp cloth (Fig. 14). A similar method was likely used for the other statues as well, although this has not been confirmed. Irises and pupils were sometimes drawn or painted onto the exterior surface of the crystals, but there is no extant example of a statue showing this technique. Although there are some statues with painted pupils, the pupils were added sometime after the statue was made, so it is difficult to know the exact technique that was originally used.

Some Korean Buddhist sculptures have stones other than rock crystal inserted to represent the eyes. The earliest example of such a sculpture is the stone standing bodhisattva from Gwanchoksa Temple in Buyeo, South Chungcheong Province, which features a black stone (perhaps obsidian or shale) that was smoothed and inserted from the outside (Fig. 15). The method of using rock crystal or another stone to simulate the eyes adds a much more naturalistic, lifelike quality than simply painting or carving the eyes, and thus is probably associated with the belief that the Buddha was a living person with a corporeal body. It is also related to the practice of installing objects inside a statue. Yi San (李㦃), a fourteenth-century Goryeo literati, wrote a text entitled “On Gold-Painting the Maitreya Triad from Geumjangsa Temple in Mt. Yongdu” (龍頭山 金藏寺 金堂主彌勒 三尊改金記), in which he described several steps involved in the restoration process: “...shaping clay, sculpting wood, gilding the triad, replacing the eyes with blue beads, replacing and renewing everything, including the crown, necklace, robe, etc…..” (Dongmunseon). Thus, it would seem that blue beads were sometimes used to make the eyes, indicating the prevalence of this practice during the Goryeo Dynasty.

In Japan, the eyes are sometimes represented with black ink or colored pigments, but some sculptures have eyes made of rock crystal or glass, which are held in place with bamboo pegs (Mitsumori Masashi and Okada Ken 1996, 105-106). Within China, there are very few extant wooden Buddhist sculptures from the Song Dynasty, and the history of this technique has not been the subject of much research, so it is difficult to know just when the technique first appeared. The only known instance is a sculpture of the Buddha from the Liao Dynasty, which has ceramic pieces inserted for the eyes, reminiscent of the monumental sculpture of the Buddha from Cave 20 of the Yungang Grottoes (near Datong, Shanxi province) of the Northern Wei Dynasty. In fact, the finest extant examples of wooden Buddhist sculptures from the Southern Song period are now housed in Japan, and they have been examined in detail.

Based on evidence from extant Buddhist sculptures, it is believed that the gamtang technique and the use of rock crystal for the eyes were both imported into Goryeo from Song. For example, two sculptures from the Southern Song period that are currently in Japan—a wooden bodhisattva from Seiunji Temple in Kanagawa (Fig. 9) and a wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Sennyuji Temple in Kyoto (Figs. 8a and 8b)—have hair made with a material similar to gamtang. In particular, the hair of the sculpture from Sennyuji Temple closely resembles that of the ones from Goryeo made with conjoined strips of the pliable material. The bodhisattva from Seiunji Temple also has green rock crystal or green glass inserted from the inside the forehead, which is similar to Yi San’s description of using a colored stone or beads to represent the eyes. Thus, the extant examples would seem to indicate that the use of gamtang and rock-crystal eyes first appeared during the Goryeo Dynasty in Korea and during the Southern Song period in China. Nonetheless, more precise details about the differences and affinities between techniques and materials have yet to be determined.

Fig. 8a. Head of Fig. 8. Ningbo, the Holy Place (聖地寧波). (Nara: Nara National Museum, 2009, Fig. 87).

Fig. 8b. Side view of Fig. 8. Ningbo, the Holy Place (聖地寧波). (Nara: Nara National Museum, 2009, Fig. 87).

Form and Technique of Crowns

Two representative crowns for mid-Goryeo-period sculptures of bodhisattva can be seen in the gilt bronze seated bodhisattva from Daeheungsa Temple in Haenam (Fig. 2a) and the wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bogwangsa Temple in Andong (Fig. 12e). Both the form and the technique for making these crowns is unique among Goryeo Buddhist sculptures. The gilt crown of the sculpture from Bogwangsa Temple is made primarily from copper (83.1%) and zinc (10.86%). It is extravagantly decorated with scroll and lotus designs and various inset jewels, including sardonyx and turquoise, though most of the jewels have been lost. The tiny Nirmana-Buddha was made separately and attached to the small wooden panel at the center of the crown. The front of the crown consists of three separate pieces that were joined together with rivets and then attached to the back of the crown. The lower rim (Fig. 12f) is decorated with a pattern of squares and several lotus blossoms, which were made separately and appliqued, exemplifying advanced metalworking techniques. The lotus blossoms are depicted as buds about to burst into full bloom, which is characteristic of lotus designs from the Goryeo Dynasty.

Fig. 12e. Crown of wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Bogwangsa. (Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage).

Although no crown with this exact form has ever been found in China, the overall composition of the scroll and lotus design was a common motif from the Northern and into the Southern Song period. For instance, similar designs can be seen on the crowns of bodhisattvas sculpted in the grottoes of Anyue and Dazu in Sichuan Province. Notably, those crowns also feature an arrangement of lotus flowers on the front. In addition, the overall style of crown, with multiple pieces and points spreading outward (like a blooming f lower), is reminiscent of the crowns of two different Buddhist sculptures from China: the bodhisattva statue from the Hall of Three Great Bodhisattvas in Chongqingsi Temple in Zhangzi, Shanxi Province (1079) and the bronze Samantabhadra Bodhisattva statue from Wanniansi Temple on Mt. Emei, Sichuan Province (980) (Fig. 16). A similar crown also appears in the depiction of a bodhisattva in Pure Land of Amitabha from Chionin, Kyoto (1180, Fig. 17). Other crowns that feature a lower band decorated with the quadrilateral design include that of the Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva in Cienyan (賜恩岩) Temple in Mt. Qingyuan, Quanzhou, and that of a stone bodhisattva from Nantiansi Temple, Jinjiang, Fujian Province (1216). In addition, the crown of a wooden seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Sennyuji Temple, Kyoto (Fig. 8) has its lower rim decorated with circular motifs rather than lotus flowers. This evidence indicates that the style of crown of Goryeo bodhisattva sculptures reflects the influence of the Northern and Southern Song.

Fig. 16. Bronze Samantabhadra Bodhisattva statue from the Hall of Amitabha Buddha in Wanniansi Temple on Mt. Emei, Sichuan Province. 980. Chinese Sculpture by Angela Falco Howard, Li Song, Wu Hong, Yang Hong. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006, plate 4.23).

Fig. 17. Pure Land of Amitabha from Chionin, Kyoto. Southern Song Dynasty, 1180. Colors on silk, 150.5 x 92.0 cm. Ningbo, the Holy Place (聖地寧波). (Nara: Nara National Museum, 2009, Fig. 57).

Very few extant bodhisattva statues of the mid-Goryeo period have crowns. However, related examples can be found among sculptures from the late Goryeo and early Joseon periods, including a seated bodhisattva from Gaesimsa Temple, a gilt bronze standing bodhisattva in the National Museum of Korea, a dry-lacquer seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Naksansa Temple, and a copper crown currently located in Takuzudama Shrine in Tsushima Island, Japan (Fig. 18). All of these crowns were produced between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and are comparable to the previously discussed crowns, in that they are formed by combining separate pieces and that they feature an openwork scroll design. Hence, the style and form of crowns that were likely introduced from the Song Dynasty during the mid-Goryeo period continued to be widely produced in the late Goryeo period.

Selection of the Maritime Route and Iconography

Most of the Goryeo Buddhist sculptures discussed thus far have been sculptures of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva. Figure 19 shows the sites where most of those Goryeo Avalokiteshvara sculptures were excavated and enshrined. Notably, almost all of these sites—including Gangjin and Haenam (South Jeolla Province), Seocheon and Haemi (South Chungcheong Province), and Gaeseong (Goryeo’s capital)—were prominent port cities that regularly received ships from Song. Two other excavation sites—Andong and Bonghwa (North Gyeongsang Province)—are located in an area of the Namhan and Nakdong Rivers, near the Joryeong Pass, which was the primary access route for ground traffic moving from the south to Hanyang (present-day Seoul) and Gaeseong. During the Goryeo Dynasty, this area was known to have many temples that were dedicated to deceased members of the royal family, including Bongjeongsa, Bogwangsa, and Yongmunsa Temples in Andong. Similar temples could also be found in Seocheon, Gangjin, and Haenam, all of which are located near the coast. Thus, all of these areas were located in proximity to maritime transportation routes, and all had various temples dedicated to deceased members of the royal family or the aristocracy.

The fact that so many of these sculptures display aesthetic features from the Northern and Southern Song can be attributed to the location of the cities along maritime routes to China. During the early Goryeo period, there were at least two main routes to China. In the early Goryeo, the primary route went through Dengzhou (Shandong Province) and then on to Kaifeng (the capital of Northern Song, in Henan Province). This was the route traversed by the Great Monk Uicheon for his trip from Goryeo to Song in 1085. It is also known that a Goryeo official named Kim Je (金悌) traveled to Song via Dengzhou in 1071 in order to present a tribute prior to the resumption of full diplomatic relations in 1072.

However, as evinced by a passage in Goryeosa1, a southern route was also in use around the same time, starting from the Yeseong River (Gaeseong), to Heuksando Island, and then passing through Mingzhou (present-day Ningbo, Zhejiang Province) and Quanzhou (Fujian Province), eventually arriving at Kaifeng (Fig. 20). According to Goryeosa, a Song merchant named Huang Shen delivered a diplomatic document to Fujian, which was located south of the aforementioned route through Shandong Province. As such, it would seem that the maritime routes through both Shandong and Fujian were in use at that time.

Some of the posts along the routes included Gangjin, Haenam, and Seocheon, which also happened to be the main production sites of Goryeo ceramics. In particular, during the Goryeo Dynasty, Jeolla Province served as the primary point of departure for routes crossing south of the Yellow Sea or East China Sea, which were the preferred ways into Hangzhou or Mingzhou (Zhejiang Province) (Yun Myeongcheol 2009, 223-225). Gangjin was not only a main port of Jeolla Province, but also provided access to other major ports, including Haenam, Jangheung, Yeongam, and Wando. As the center of the Goryeo ceramic industry and a crucial transportation hub, Gangjin was ideally suited to receive aesthetic influence from Song.

Notably, Buddhist sculpture produced in Mingzhou made its way into Japan. For example, a wooden sculpture of a seated Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva (Fig. 8) was brought from Bailiansi Temple in Mingzhou to Sennyuji Temple in Kyoto by a Japanese monk named Tankai (湛海). Records show that Tankai went to China in 1230 to commission the sculpture, which he then brought back to Japan in 1250. Furthermore, the record states that the statue was originally f lanked by standing sculptures of Skanda and Somachattra, and that the hall where it was enshrined was decorated like Mt. Potalaka, confirming that the depicted figure is the Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara. Another wooden bodhisattva from Hoonji Temple in Hyogo (Fig. 10) is known to have been made by a Mingzhou sculptor named Shin Ichiro (沈一郞), and brought to Japan in 1237 (Tsuda Tetsuei and Sarai Mai 2006, 48-54; Jeong Eunwoo 2008, 194-198). Furthermore, Wudenghuiyuan (五燈會元, Compendium of the Five Lamps), written by a Song monk named Puji (普濟, 1179-1253), states that someone from Goryeo went to Mingzhou and ordered the production of a sculpture of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva. Although he intended to take the statue back to Goryeo, he eventually had to stay in Kaiyuansi Temple in Mingzhou because of problems with his ship (Jang Dongik 2000, 413-414).2 This record demonstrates that Avalokiteshvara sculptures from Mingzhou were brought into Goryeo; it is believed that this was a fairly common practice in East Asia at the time.

There is a similar story involving the Japanese monk Egaku (惠萼), who in 858 acquired a sculpture of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva from Mt. Wutai in Shanxi Province, and attempted to take it back to Japan. However, the ship that he took from Mingzhou became stranded, and Egaku interpreted this as a sign that the statue should not be taken to Japan. Thus, he enshrined the statue in a small temple near Mt. Putuo (Taniguchi Kosei 2009, 14-15). These stories demonstrate the overall popularity of faith in Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, the large-scale production of Avalokiteshvara sculptures during the Song Dynasty, and the tendency of people from Goryeo and Japan to acquire such sculptures and take them back to their home countries.

It is crucial to note that both of these historical records document sculptures of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, and that the extant sculptures in Korea and Japan are also Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva. The wide production of Avalokiteshvara sculptures in Mingzhou can be attributed to the city’s close proximity to Mt. Putuo and Mt. Luojia, two holy sites of the Avalokiteshvara faith named after the legendary Mt. Potalaka. Mt. Putuo in particular has flourished as a sacred location amongst the followers of Avalokiteshvara since the Southern Song period. Mt. Putuo was believed to have strong auspicious powers, so people regularly went there to pray for a safe voyage, particularly when traveling by sea. Hence, people sailing to Korea or Japan likely would have stopped there to pray for a safe journey. In fact, sculptures of Avalokiteshvara were thought to have protective powers, and, as such, were often prominently placed on the prow of a ship. It seems likely that these beliefs were also prevalent in Goryeo, given the state’s reverence for both the Lotus Sutra and Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, and the wide production of Avalokiteshvara sculptures.

During the Goryeo Dynasty, paintings of Avalokiteshvara were also widely used, as documented in Gujin huajian (古今畫鑑, Examination of Painting) by Tang Hou (湯垕, active in the early fourteenth century), and Tuhui baojian (圖繪寶鑑, Precious Mirror for Examining Painting) by Xia Wenyan (夏文彦, active in the late fourteenth century) of the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368). According to those records, “Avalokiteshvara paintings of Goryeo are very elaborate. They are based on the masterful strokes of Weichi Yiseng (㷉遟乙僧, active in the seventh century), a monk painter of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), although they achieve their own subtlety and beauty”3 (Huang Binhong and Deng Shi 1986, 1389). These records reflect the popularity of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva and the technical refinement and development of Goryeo artists.

Conclusion

This paper has examined some features of Buddhist sculptures from the mid-Goryeo period that reflect the influence of the Song Dynasty, including bodhisattvas depicted in the posture of royal ease, the use of gamtang to form hair and jewels, the insertion of rock crystal for the eyes, and the composite crowns made from multiple thin pieces of metal. Through maritime routes, the Avalokiteshvara faith associated with Mt. Putuo in China was introduced to Goryeo, leading to the widespread production of sculptures of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva. Goryeo Buddhist sculpture is world-renowned for its beauty and refinement, which is directly related to the afore-mentioned features. For example, the application of gamtang on wooden or dry-lacquer surface allowed for a delicate, elaborate rendering of hair and jewels. The crowns, assembled from several thin sheets of copper, demonstrate amazing expertise and precision in metalworking. Glass, rock crystal, and other dazzling jewels were carefully inserted to represent the eyes. Used together, these techniques yielded the overall excellence for which Goryeo Buddhist sculpture is renowned. All of these stylistic and technical elements likely were introduced to Goryeo from Song via maritime routes. Of course, these new methods were refined by Goryeo artisans and combined with existing techniques to create a new aesthetic that was unique to Goryeo.

Mid-Goryeo and Song Buddhist sculptures are alike in terms of their formal and stylistic elements, as well as their production techniques. Such affinities confirm that Goryeo Buddhist sculpture was not based solely on imported Buddhist sculptures or albums of Buddhist paintings. Goryeo sought sculptors from Song, and dispatched their own artisans to there to copy Buddhist murals. Goryeo sculptors actively and directly incorporated elements of Song Buddhist sculpture into their own culture, and this passion still reverberates today through the extant Buddhist sculptures of Goryeo.

Footnote

Selected Bibliography

Moon, Myunngdae (문명대). 1996. “Goryeo 13 segi jogagyangsik gwa gaeunsajang chwibongsa mogamitabulsang ui yeongu” (고려 13세기 조각양식과 개운사장 취봉사 목아미타불상의 연구, “Study on Wooden Amitabha Buddha Image Dated 1274 CE Documented to Be Made in Chwibongsa Temple Currently Housed in Gaeunsa Temple ”). Gangjwa misulsa (강좌미술사, Journal of Art History Research Institute of Korea) 8, 37-57.

Son, Yeongmun(손영문). 2009. “Andong bogwangsa mokjog - waneumbosaljwasang yeongu ” (안동 보광사 목조관음보살좌상 연구, “Study of Wooden Seated Avalokitesvara of Bogwangsa Temple in Andong ”). Andong bogwangsa mokjogwaneum - bosaljwasang (안동 보광사 목조관음보살좌상, Wooden Seated Avalokitesvara of Bogwangsa Temple in Andong). Daejeon: Cultural Heritage Administration Korea; Seoul: Research Institute of Buddhist Cultural Heritage.

Yun, Myeongcheol (윤명철). 2009. “Cheongjasaneop gwa gwallyeondoen goryeo ui daeoe hangno ” (청자산업과 관련된 고려의 대외 항로, “Goryeo ’s Maritime Route Related to the Celadon Industry ”). Goryeocheongja bomulseon gwa gangjin (고려청자 보물선과 강진, Goryeo Celadon Shipwreck and Gangjin). Mokpo: National Research Institute of Maritime Cultural Heritage.

- 1201Download

- 2639Viewed

Other articles from this issue

- Editorial Note

- Form and References of the Goryeo Painting of the Rocana1 Assembly in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Hyeonwangdo from Seongbulsa Temple and the Tradition of Hyeonwangdo of the Joseon Dynasty

- History of the Bokjang Tradition in Korea

- Production Specialization of Liaoning- and Korean-type Bronze Daggers during the Korean Bronze Age

- Archaeological Evidence of Goguryeo’s Southern Expansion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries

- The Ksitigarbha Triad from Gwaneumjeon Hall at Hwagyesa Temple and Court Patronage of Buddhist Art in the Nineteenth Century