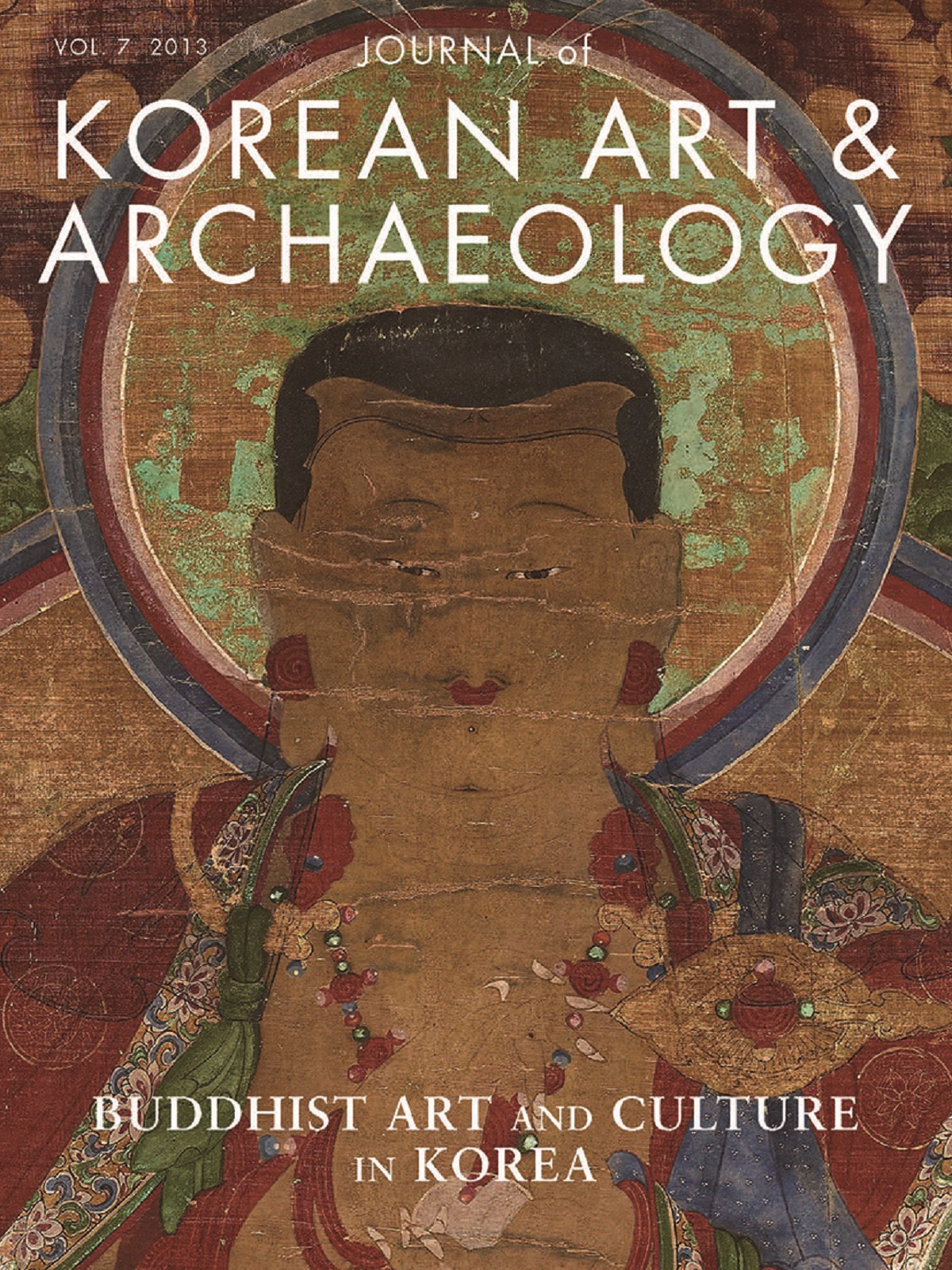

Journal of Korean Art & Archaeology 2013, Vol.7 pp.2-5

Copyright & License

As the senior editor of the Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology, articles from leading Korean archaeologists and art historians span from the Late Bronze Age to the 19th century. Highlights include studies on Korean Buddhist art and its Chinese influences, the evolution of the bokjang tradition, specialization in Korean Bronze Age daggers, Goguryeo's Southern expansion, and 19th-century royal patronage of Buddhist temples. These articles exemplify scholarly excellence, combining research and quality translations for an insightful publication.

It is an honor and a pleasure to serve as senior editor of the Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology. During his tenure as senior editor, Roderick Whitfield set a standard of excellence difficult to match; even so, the articles accepted by the editorial committee for publication in the Journal are of a quality that they speak for themselves, just as the excellence of the English translations speak to the advanced skills of the translators, making the editor’s work a joy of scholarship.

Written by leading Korean archaeologists and art historians, who serve as university professors, museum curators, and researchers at archaeological centers, the articles in this issue of the Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology span a broad chronological range from the Late Bronze Age and into the nineteenth century. They also examine works in a variety of media, from Bronze Age daggers and Goguryeo tombs to Buddhist sculptures and paintings from the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties to the ritualistic installation of various objects inside Buddhist images (both sculptures and paintings) to royal patronage of Buddhist temples in the late Joseon era.

A transformation tableau of Yuanjue jing, or the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment—a painting in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston that was long believed to be Chinese but that has now been identified as a Korean painting from the late Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392)—is the subject of “Form and References of the Goryeo Painting of the Rocana Assembly in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston”. To explain the iconography and background of the Boston scroll, Chang Qing focuses on the Rocana triad, or images of the Rocana assembly, and traces the lineage of the Goryeo painting back to China. Scholars have previously identified a number of similar Rocana triad images in Sichuan, Hangzhou, and Japan, and have asserted that icons of this type derive from Chinese images produced for the Huayan, or Avatamsaka, Sect of Buddhism in the Five Dynasties (907-960) and Song (960-1279) periods. Since most of the related images are found in Sichuan, some scholars have speculated that Sichuan might be the likely origin of the iconography. However, the earliest extant similar image is located in Hangzhou, which has traditionally enjoyed a much higher status than the Southwest of China, in terms of both religion and culture. As Hangzhou was then the nation’s primary political and Buddhist center, the images found in Hangzhou should be the key to understanding the iconography and background of the Boston Goryeo scroll. In this article, Chang analyzes the transmission of Huayan Buddhist art from China to Korea by focusing on the iconography of the Boston Goryeo scroll and the Rocana assembly found in niche 5 of Feilaifeng in Hangzhou. He further discusses how artists inherited the tradition and created unique features for the Rocana assembly, as well as how Hangzhou played an important role in the transmission of Huayan Buddhist images.

In “Hyeonwangdo from Seongbulsa Temple and the Tradition of Hyeonwangdo of the Joseon Dynasty”, Jeong Myounghee closely examines the Hyeonwangdo, or painting of King Yama, the fifth king of the ten kings of the underworld, which was painted for Seongbulsa Temple in 1798 and is now housed in the National Museum of Korea, Seoul. Her research provides details about the background, production, and function of Hyeonwangdo during the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). Understanding of this particular painting was greatly enhanced in March 2005, when, during conservation treatment, several objects and a document entitled Hyeonwangtaeng wonmun were found inside the scroll’s upper shaft. Through a document called Hyeonwangcheong, which is a liturgy of the formal procedures for performing the ritual for Hyeonwang, and through a ritual called “Hyeonwangjae” (final ritual for Hyeonwang), Jeong investigates how the practices of worshipping, making offerings, and praying to Hyeonwang became formalized and institutionalized. She also explores how Hyeonwangdo developed separately from Siwangdo, or paintings of the ten kings of the underworld through the process of formalization. Until now Hyeonwangdo have been neglected by scholars of Buddhist art, who typically have considered them to be merely a subgenre of paintings depicting the underworld. Notably, however, while other paintings of the underworld were typically enshrined in the Judgment Hall, Hyeonwangdo were often enshrined in the temple’s main hall. In focusing on Hyeongwangdo, Jeong also examines how Buddhist paintings with the same theme acquired differing religious meanings, depending on where they were enshrined.

In “Mid-Goryeo Buddhist Sculpture and the Influence of Song-Dynasty China”, Jeong Eunwoo examines characteristics of Korean Buddhist sculptures from the mid-Goryeo period that reflect the influence of China’s Song Dynasty (960-1279), including bodhisattvas depicted in the posture of royal ease, the use of gamtang—a pliable substance presumably comprised of wax, pine resin, and other ingredients—to form hair and jewels, the insertion of rock crystal for the eyes, and use of composite crowns made from multiple thin pieces of metal. Through maritime routes, the Avalokiteshvara faith associated with Mt. Putuo in China was introduced to Goryeo (918-1392), leading to the widespread production of sculptures of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva. The world-renowned beauty and refinement of Goryeo Buddhist sculpture is directly related to the employment of such features and techniques from Song-Dynasty China. The application of gamtang on wooden or dry-lacquer surfaces allowed for a delicate, elaborate rendering of hair and jewels, for example, and the crowns, which were assembled from thin sheets of copper, attest to precision in metalworking. Glass, rock crystal, and other dazzling jewels were carefully inserted to represent the eyes. Used together, these techniques imparted the excellence for which Goryeo Buddhist sculpture is well known. All of these stylistic and technical elements likely were introduced to Goryeo from Song China via maritime routes. Of course, these new methods were refined by Goryeo artisans and combined with existing techniques to create a new aesthetic that was unique to Goryeo.

Bokjang—the ritualistic installation of various objects inside a Buddhist image—is the topic of “History of the Bokjang Tradition in Korea” by Lee Seonyong. Buddhist images, whether sculptures or paintings, only become objects of faith and worship through two rituals: jeoman, wherein the pupils of the Buddha’s eyes are painted in the final stages of creating a Buddhist image, and bokjang, the ritualistic installation of various objects inside a Buddhist sculpture or painting. Virtually every country to which Buddhism has spread has a tradition similar to the Korean bokjang tradition. The exact origins of the bokjang ritual are not known, but the oldest examples known of its practice are the sixth-century Buddhas of Bamiyan, in Afghanistan (which were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001). In Korea, the earliest known example of bokjang is thought to be an agalmatolite jar dated by inscription to 766, which was discovered inside the pedestal of a stone statue of Vairocana Buddha. The first known use of the term bokjang dates to 1241 and comes from volume 25 of Dongguk Isanggukjip by Yi Gyubo (1168-1241). Based on images with dated inscriptions and on textual references, the practice of bokjang is believed to have been firmly established as a Buddhist ritual during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). In this paper, Lee examines the evolution of the Korean bokjang tradition by comparing five existing versions of the Josanggyeong Sutra, with specific reference to the main elements of bokjang from the Goryeo and Joseon (1392-1910) dynasties. Those records are compared to surviving examples of bokjangmul—the objects installed in an image—to illustrate how the procedures and contents of the ritual changed over time. Although the practice of bokjang seems initially to have begun in Korea as a way to enshrine Buddha’s relics and sutras, with the publication of the Josanggyeong Sutra, the tradition gradually developed into a practice unique to Korea, a practice that incorporated the concepts of the five directions. Despite numerous changes that took place within the bokjang tradition from Goryeo to Joseon, the core elements were always related, demonstrating that the bokjang practices of the two dynasties were interconnected.

In “Production Specialization of Liaoning- and Korean-type Bronze Daggers during the Korean Bronze Age”, Cho Daeyoun and Lee Donghee examine and compare the degree of specialization in the production of Liaoning-type and Korean-type bronze daggers in Korea’s Late Bronze Age. Their study demonstrates that relative standardization was achieved in the production of Korean-type bronze daggers in the Late Bronze Age, and that the production system became more specialized around this time. This development can be attributed to the increase in the number, diversity, and technological standard of bronze objects produced in southern Korea at that time. They present clear evidence that the demand for and production of bronze items increased significantly in the Late Bronze Age, and they argue that it thus is reasonable to assume that the production system of bronze items, including daggers, became more specialized, such specialization naturally leading to product standardization. This specialization in the production of bronze items would also have allowed for more diversity in the types of products being manufactured. That different-sized Korean-type bronze daggers were made through separate processes of production indicates that size was an important feature in the production of bronze daggers, which in turn suggests that different-sized daggers served different functions. In particular, the high degree of morphological standardization shown for large Korean-type bronze daggers might be attributed to their use as actual weapons. It can also be noted that the diversification of bronze items that took place in the Late Bronze Age led to the production of new types of bronze items, such as bronze mirrors with coarse and fine design, and ritual implements in the form of pole-top bells and eight-branched bells.

Choi Jongtaik in “Archaeological Evidence of Goguryeo’s Southern Expansion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries” explores the expansion of Goguryeo (traditionally, 37 BCE – CE 668) into southern Korea through the investigation of Goguryeo and Goguryeo-type ceramics and stone-chamber tombs excavated in and around Seoul. At present, the earliest Goguryeo artifact to have been unearthed in southern Korea is the globular jar from the site of Juwol-ri in Paju, Gyeonggi Province, which dates to the late fourth or early fifth century. Thereafter, stone-chamber tombs with horizontal entrances and elongated rectangular burial chambers appear from the mid-fifth century onward. The construction of such tombs can be understood in relation to Goguryeo’ s advancement into and annexation of the Chungju region, via the upper reaches of the Bukhan and Namhan Rivers, which took place in the late fourth century. That Goguryeo settlements have regularly been discovered in the vicinity of the tombs indicates that Goguryeo intensively and continuously maintained control over the captured territories for a substantial period of time. Archaeological remains of Goguryeo activity at several fortresses all date to the late fifth century and can be associated with Goguryeo’s attempts to maintain control over the Jinchon, Cheongwon and Daejeon areas. Finally, in the sixth century, Goguryeo forts came to be established on Mt. Acha and its environs, north of the Han River, near Seoul, and most of the forts of the Yangju Basin and the Imjin-Hantan River region also appear to date to this period.

In “The Ksitigarbha Triad from Gwaneumjeon Hall at Hwagyesa Temple and Court Patronage of Buddhist Art in the Nineteenth Century” Lee Yongyun investigates the role of court women in the royal patronage of Buddhist temples during the late Joseon period (1392-1910) and also explores individual painting styles of monk-painters active in the Seoul and Gyeonggi region during the late nineteenth century. He bases his study on the Ksitigarbha Triad, which was created in 1876 for the Gwaneumjeon Hall of Hwagyesa Temple, which is located on Mt. Samgak in Seoul. Although the Gwaneumjeon Hall of Hwagyesa Temple was destroyed by fire in 1974, the painting of Ksitigarbha originally enshrined there has been preserved and now is in the collection of the National Museum of Korea, Seoul. This painting provides a rare opportunity to examine the historical background of the construction of Gwaneumjeon Hall, including the goals of its patrons. In the late nineteenth century, Hwagyesa Temple underwent a major reconstruction project, centered around the construction of Gwaneumjeon Hall, which was built to house the Embroidered Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, which had been donated by the royal court. Notably, the donation of this icon marked a turning point in the pattern of royal patronage at the temple, wherein women of the royal court—as represented by Grand Queen Dowager Jo, Queen Dowager Hong, and Sanggung Kim Cheonjinhwa—became the main benefactors, replacing their male counterparts. Examination of the inscription on the Ksitigarbha Triad, which was originally housed in Gwaneumjeon Hall, reveals that both Grand Queen Dowager Jo and Queen Dowager Hong actively supported Hwagyesa Temple. In focusing on Sanggung Kim Cheonjinhwa, who seems to have acted as a vital emissary between Hwagyesa Temple and the royal court, this article also investigates the role of court women in the patronage of Buddhist temples in the late Joseon period. Apart from royal patronage, the Ksitigarbha Triad of Gwaneumjeon Hall at Hwagyesa Temple allows us to examine the work of Hwasan Jaegeun, a monk-painter trained at Hwagyesa Temple who was active in the capital in the late nineteenth century.

Alan J. Dworsky Curator of Chinese Art Emeritus

Harvard Art Museums

Senior Lecturer on Chinese and Korean Art

Department of the History of Art and Architecture Harvard University

- 381Download

- 777Viewed

Other articles from this issue

- Form and References of the Goryeo Painting of the Rocana1 Assembly in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Hyeonwangdo from Seongbulsa Temple and the Tradition of Hyeonwangdo of the Joseon Dynasty

- Mid-Goryeo Buddhist Sculpture and the Influence of Song-Dynasty China

- History of the Bokjang Tradition in Korea

- Production Specialization of Liaoning- and Korean-type Bronze Daggers during the Korean Bronze Age

- Archaeological Evidence of Goguryeo’s Southern Expansion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries

- The Ksitigarbha Triad from Gwaneumjeon Hall at Hwagyesa Temple and Court Patronage of Buddhist Art in the Nineteenth Century