Journal of Korean Art and Archaeology Vol.14

2020. 01.

2577-9842

2951-4983

INTRODUCE

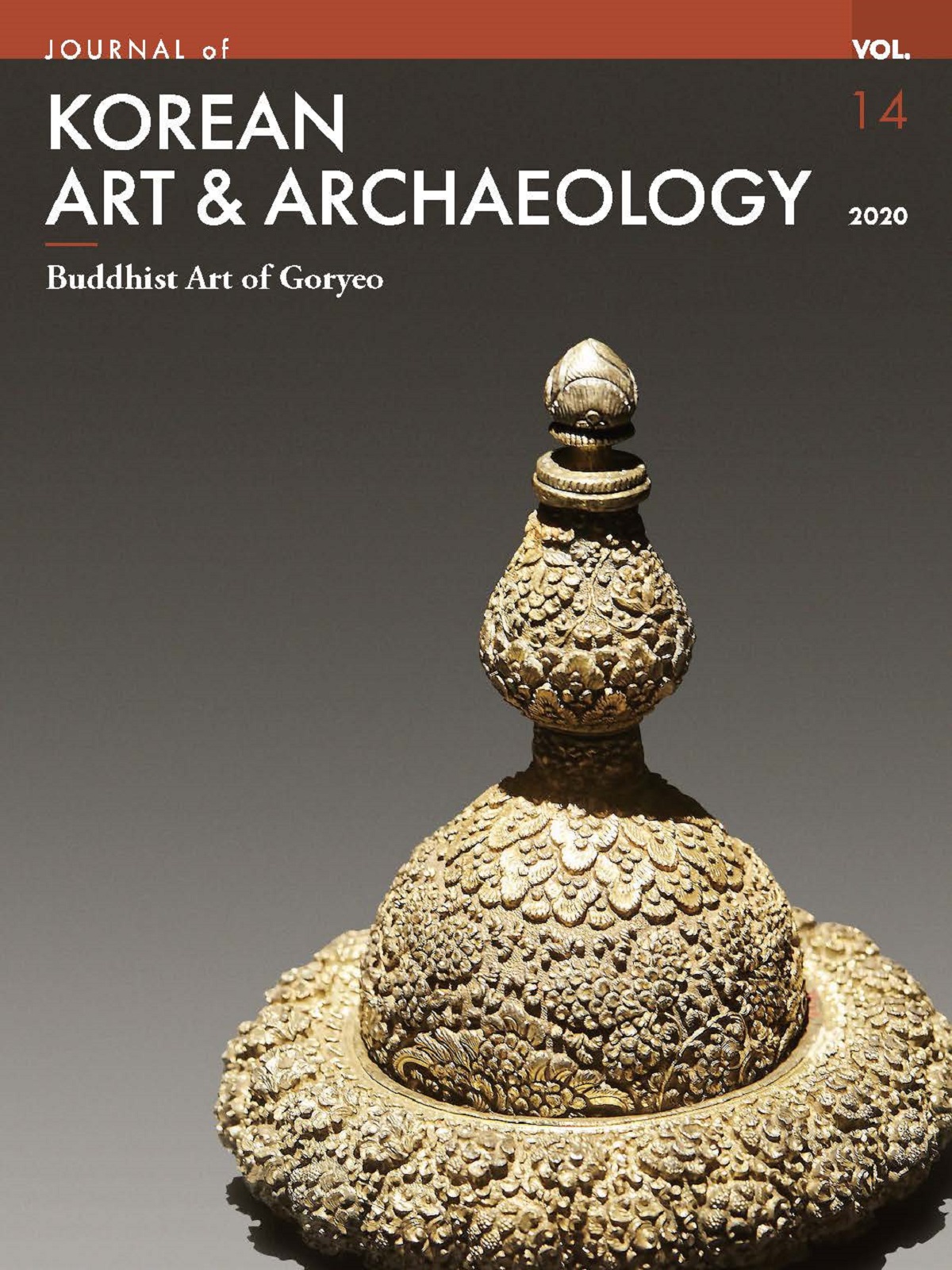

- Buddhist Art of Goryeo

- This editorial note discusses the five articles found in this issue, respectively, on Goryeo metalwork, Goryeo Buddhist sculpture, Goryeo Buddhist rituals, votive objects related to ritual objects enshrined inside Goryeo Buddhist sculptures, and textiles in Goryeo Buddhist paintings. Choi Eung Chon’s article entitled “Diverse Aspects and Characteristics of the Goryeo Dynasty Crafts in Xuanhe Fengshi Gaoli Tujing” analyzes the records on crafts from this era found in Gaoli tujing, a report written by the Chinese emissary Xu Jing in 1123. This paper largely categorizes crafts into najeon chilgi (mother-of-pearl lacquerware), textiles, woodworking, and metalwork. Notably, metal items, which make up the majority of surviving Goryeo crafts, are examined in detail in terms of their forms and uses. The brief inclusion of the phrase “praiseworthy elaboration” (細密可貴) on najeon in Gaoli tujing suggests that Goryeo mother-of-pearl wares created using tortoiseshell (daemo) painted using the bokchae (reverse-side coloring) technique, which was considered the most sophisticated method of the time, were exported to foreign countries. This paper classifies metalwork according to its shapes and uses, regardless of the order in Gaoli tujing. Gaoli tujing remarks on the diverse shapes of incense burners, the increased production of vessels modeled after ancient bronzewares (including incense burners in the shape of Boshan Mountain), and braziers. It also hints at the extensive production of gwangmyeongdae candle holders (光明臺) and helps with the investigation of lighting appliances, such as candles, of the Goryeo dynasty. Furthermore, Gaoli tujing mentions a few types of Buddhist metalwork, including ritual ewers (kundika), the large bell hanging at Bojesa Temple (普濟寺), Buddhist flagpoles (幢竿, danggan), and vajras. Ritual ewers are specifically discussed, providing valuable information for dating Goryeo ritual ewers produced at the time. According to Gaoli tujing, a large bell decorated with a pair of $ying immortals was created in 1094 and hung at Bojesa Temple, the proto-temple for Yeonboksa Temple (演福寺), before the so-called bell of Yeonboksa Temple was installed. It further describes a copper Buddhist $agpole that stood in the precincts of Heungguksa Temple (興國寺) and was adorned with bonghwang (a pair of mythical birds, Ch. fenghuang) heads bearing a silk banner, something which had not been seen before. This record provides important material for restoring Goryeo Buddhist flagpoles to their original form. It is also noteworthy that such flagpoles were called beon-gan (幡竿) at the time. Moreover, the record of a gilt vajra being carried by a wangsa (王師, royal preceptor) proves that a vajra was regarded as an attribute of a monk from early on. Although the original drawings included in Xu Jing’s Gaoli tujing have been lost, and its contents are rather peripheral and fragmentary, it still carries meaningful connotations by offering new perspectives and data on Goryeo crafts from 1123 that are now unrecoverable. However, its analyses of craftworks are somewhat superficial and illogical compared to the fuller analyses found in other literary sources, thus failing to provide substantial evidence on the originals. The second article “The Development of Suryukjae in Goryeo and the Significance of State-sponsored Suryukjae during the Reign of King Gongmin” by Kang Ho-sun systemically explicates the origins and execution of the Buddhist rite known as Suryukhoe (水陸會, water and land assembly) that began to be held during the Goryeo dynasty and remained significant well into the subsequent Joseon period. According to Kang, Suryukhoe were based on Siagwihoe (施餓鬼會, ceremony for feeding hungry ghosts) and served to pray for the repose of the deceased. They were held to save people from illness and assuage public sentiment even during the Joseon dynasty when Buddhism was constrained. Kang also describes how the royal court held Suryukhoe as a funeral rite in the early Joseon period and that as a result, this Buddhist ritual was included in Gyeongguk daejeon (經國大典, National code). Kang argues that the Suryukhoe of the early Joseon period derived from the national Suryukhoe that King Gongmin ordered Monk Hyegeun (惠勤), also known as Master Naong (懶翁), to perform during the funerary rite of his consort Princess Noguk-daejang at the end of the dynasty. Kang’s article is meaningful in that it expounds how the water and land assemblies, which first gained popularity during the Goryeo dynasty, continued to be held in Joseon despite this dynasty’s policy of restricting Buddhism. Kang claims that the sustained performance of Suryukhoe from the end of the Goryeo period into the early Joseon period originated in the national Suryukhoe held by King Gongmin. This assertion is based on various historical records regarding King Gongmin and Master Naong. However, Kang does not present the immediate grounds for King Gongmin’s holding of a national Suryukhoe as an element of the funeral rite. I personally believe the integration of national Suryukhoe into funeral rites could in fact have begun in the period under the rule of the Yuan dynasty, rather than during the reign of King Gongmin as suggested by Kang, given the insu&cient historical information from the Goryeo dynasty. The third article entitled “Thirteenth-century Wooden Sculptures of Amitabha Buddha from the Goryeo Dynasty and the Ink Inscriptions on their Relics,” is authored by Choe Songeun, who has performed extensive research on Buddhist sculptures from Goryeo dynasty. In this paper, Choe investigates the characteristics and production backgrounds of wooden Amitabha Buddha sculptures from the Goryeo dynasty by focusing on the Amitabha sculptures at Gaesimsa, Gaeunsa, Bongnimsa, and Suguksa Temples, within which votive objects and records have been recently discovered. Choe also provides an overview of the Goryeo Buddhist culture and on the creation backgrounds of these four sculptures by comprehensively examining their sculptural styles and the dharanis, ink inscriptions, and scriptures found inside them. Choe sheds light on the relation between the Goryeo royal court and the temporarily established office known as Seungjaesaek through an analysis of the ink inscription on the wooden plug used to seal a hole on the Wooden Seated Amitabha Buddha at Gaesimsa Temple. For the version at Gaeunsa Temple, she attempts to draw diverse historical inferences based on its prayer texts by identifying the commissioners and donors. Moreover, Choe discusses the relationship between the Wooden Seated Amitabha Buddha at Bongnimsa Temple and the historical figure Choe U, who played a leading role during the military regime that ruled Goryeo by analyzing documents extracted from the sculpture. The author additionally suggests the relevance of the Wooden Seated Amitabha Buddha at Suguksa Temple to local families in Dongju (present-day Cheolwon) and its enshrinement background by scrutinizing the dharanis placed inside it. Furthermore, Choe argues that the proliferation of Amitabha Buddha sculptures was primarily a response to the devastation inflicted during the Mongol Invasions of Korea and that the expansion of demand for Buddhist sculptures led to both the increased use of wood due to its availability as a material and to the production of uniform styles. This article is academically stimulating since the author researches a broad range of subjects spanning from the particulars of Buddhist sculpture to their materials and offers new suggestions based on historical inferences. Although her effort to present a range of possibilities is praiseworthy, there seems insufficient evidence for absolutely proving these prospects. Some readers may think that her paper does not provide enough evidence for the argument that the seated sculptures of Amitabha Buddha at Gaesimsa and Suguksa Temples could have been produced in the same workshop due to their stylistic similarity. If such a case, I would suggest referring to her Korean paper on the same theme, which provides convincing proof and detailed elucidation of the sculptural styles involved.1 In her article “Consecrating the Buddha: The Formation of the Bokjang Ritual during the Goryeo Period,” Lee Seunghye examines the sacred objects interred in the interior spaces of Buddhist sculptures during the Goryeo dynasty to illuminate the background and meaning of the contemplation of Buddha images. The author points out that interpreting these votive objects from Goryeo Buddhist images according to Josang gyeong (造像經, Sutras on the production of buddhist images), published during the Joseon dynasty, raises several issues. Lee instead reconsiders votive objects and related documents from the mid-Goryeo period and the cultural exchanges between Goryeo and the Liao dynasty, which maintained a close relationship with Goryeo during the eleventh and twelfth centuries. In particular, she reassesses the impacts of Miaojixiang pingdeng mimi zuishang guanmen dajiaowang jing (妙吉祥平等祕密最上觀門大敎王經, Sutra on the king of the great teaching of visualization methods which are auspicious, universal, secret, and superlative), which was embraced by Goryeo in the eleventh century and also quoted in Josang gyeong on the development of the rituals for enshrining sacred objects within Buddhist sculptures at the time. The sutra, translated by the monk Maitribhadra (慈賢, Ch. Cixian, K. Jahyeon) and cited as Myogilsang daegyowang gyeong (妙吉祥大敎王經) in Josang gyeong, has been considered to record the ritual for and order of filling the five treasure bottles (五寳甁, obobyeong), the core of the objects placed inside Buddhist sculptures during the Goryeo dynasty. However, Lee argues that in fact, it originally detailed the abhiseka (灌頂, initiation) rite of practitioners, not the five treasure bottles . Moreover, the author emp…

Choi Eung Chon Professor, Dongguk University

COPYRIGHT & LICENSE

To purchase a print version of this volume >>

GO TO KONGNPARK.COM- Choi Eung Chon(Professor, Dongguk University)

Goryeo art is distinguished by its cultural diversity and innovative techniques, leading to the creation of a unique Korean Buddhist art. The period saw a proliferation of Buddhist temples and various metalworks to support complex rituals. Goryeo crafts, especially metalworks, featured najeon (mother-of-pearl inlay) and silver inlay techniques. Notably, Xu Jing's 1123 account, Gaoli tujing, praised Goryeo metalwork. The dynasty also developed distinctive Buddhist rituals and sculptures. Goryeo Buddhist art, including textiles, evolved to embrace native styles and aesthetics, contributing to the rich, aristocratic, yet humble allure of Goryeo art that resonated with the public's aspirations.

- Choi Eung Chon(Professor, Dongguk University)

The Goryeo dynasty (918-1392) in Korea was a pivotal period for artistic and craft developments, particularly in metalwork and mother-of-pearl lacquerware. Influenced by diverse foreign cultures, the era saw unique Korean styles emerge, especially through Buddhist influences, leading to diverse and intricate religious metalworks. The "Gaoli tujing," an illustrated record by Xu Jing, provides critical insight into Goryeo’s crafts, detailing their sophistication and aesthetic value. This includes descriptions of items like incense burners, kendikas, and najeon chilgi (mother-of-pearl lacquerware), which demonstrate the upscale techniques and artistry achieved during this period. While Xu Jing's work reflects a foreigner's perspective, it is invaluable in understanding 12th-century Goryeo crafts, their foreign admiration, and their evolution over time.

- Kang Ho-sun(Professor, Sungshin Women’s University)

Suryukjae, a Buddhist rite for delivering souls of water and land creatures, emerged in East Asia during the Tang dynasty (618-907). Although rumored to have originated in the Liang dynasty, its practice is confirmed from the Song dynasty onward. In Korea, it was recognized by King Gwangjong (949-975) and further institutionalized during the Joseon dynasty. This rite, which transcended Buddhist sects, served to guide souls to heaven and ease the suffering from diseases. Research suggests it became significant during the reign of King Gongmin (1351-1374). The evolving Suryukjae reflected cultural exchanges between Goryeo, China, and the adaptation of Buddhist rituals in state affairs. By Joseon, Suryukjae was the primary state-sponsored Buddhist rite until Buddhism's decline in the 16th century.

- Choe Songeun(Professor, Duksung Women’s University)

Research on late-Goryeo Buddhist sculptures has emphasized 13th- and 14th-century wooden and gilt-bronze pieces, offering insights into art history and Buddhist practices. These sculptures, filled with sacred items and inscriptions, have undergone extensive stylistic and technical studies since the 1980s. This article analyzes various thirteenth-century Amitabha Buddha sculptures, including those from Gaesimsa and Gaeunsa temples, noting their shared stylistic traits and historical context. The sculptures represent widespread devotion to Amitabha Buddha during the Goryeo period, linked to the aftermath of the Mongol invasions, which led to the restoration of many Buddhist items. The uniformity in style among these wooden sculptures reflects both standardized artistic practices and a surge in the Amitabha faith, spanning diverse societal levels.

- Lee Seunghye(Curator, Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art)

In Korean Buddhism, bokjang refers to rituals for consecrating Buddhist images, established as early as the mid-12th century during the Goryeo dynasty. Guided by the Sutras on the Production of Buddhist Images from the Joseon period, bokjang involves enshrining objects like relics and silks of five colors in a Buddhist image, transforming it into a worship object. The notable feature of bokjang is the five treasure bottles, derived from esoteric texts transmitted from Liao Buddhist traditions, symbolizing the five directional Buddhas. The bokjang ritual places these bottles permanently within the image, differing from other Buddhist regions' rituals. This unique method highlights the integration of late Indian esoteric Buddhist elements within Korean practices during cultural exchanges between the Liao and Goryeo dynasties.

- Sim Yeonok(Professor, Korea National University of Cultural Heritage)

Buddhist paintings from Korea's Goryeo dynasty (918-1392) are celebrated for their artistic and historical value. These artworks provide insights into the clothing trends of the era, particularly through depictions of the bodhisattva Water-moon Avalokitesvara, known for intricate textile patterns. While studies have focused on the art historical aspects of these paintings, this research examines the types of textiles and patterns, comparing them with contemporary Chinese and Korean examples. Patterns on Avalokitesvara's garments include wave, lattice, hexagon, and pomegranate motifs. The study also delves into the weaving techniques of Goryeo textiles, like geum (compound weave silk) and ra (complex gauze silk), to reproduce key clothing elements. The findings highlight the realism of these paintings, reflecting the sophisticated textiles of the Goryeo with an emphasis on religious devotion.

- Yu Heisun(Head of Division of Conservation Science),

- Ro Jihyun(Curator, National Museum of Korea)

The ancient gold buckle from Seogam-ri Tomb No. 9 in Korea, estimated from the first or second century, showcases advanced craftsmanship including granulation. Scientific analyses through XRF, radiography, microscopy, and SEM-EDS reveal its composition and technique. The buckle is primarily 22.8K gold, with some parts reaching 23.8K. Gold granules and wires were bonded using copper diffusion, a rare method in Korea but known in Mongolian artifacts. This, along with decorative techniques, could indicate cultural exchanges and may help determine its origin.