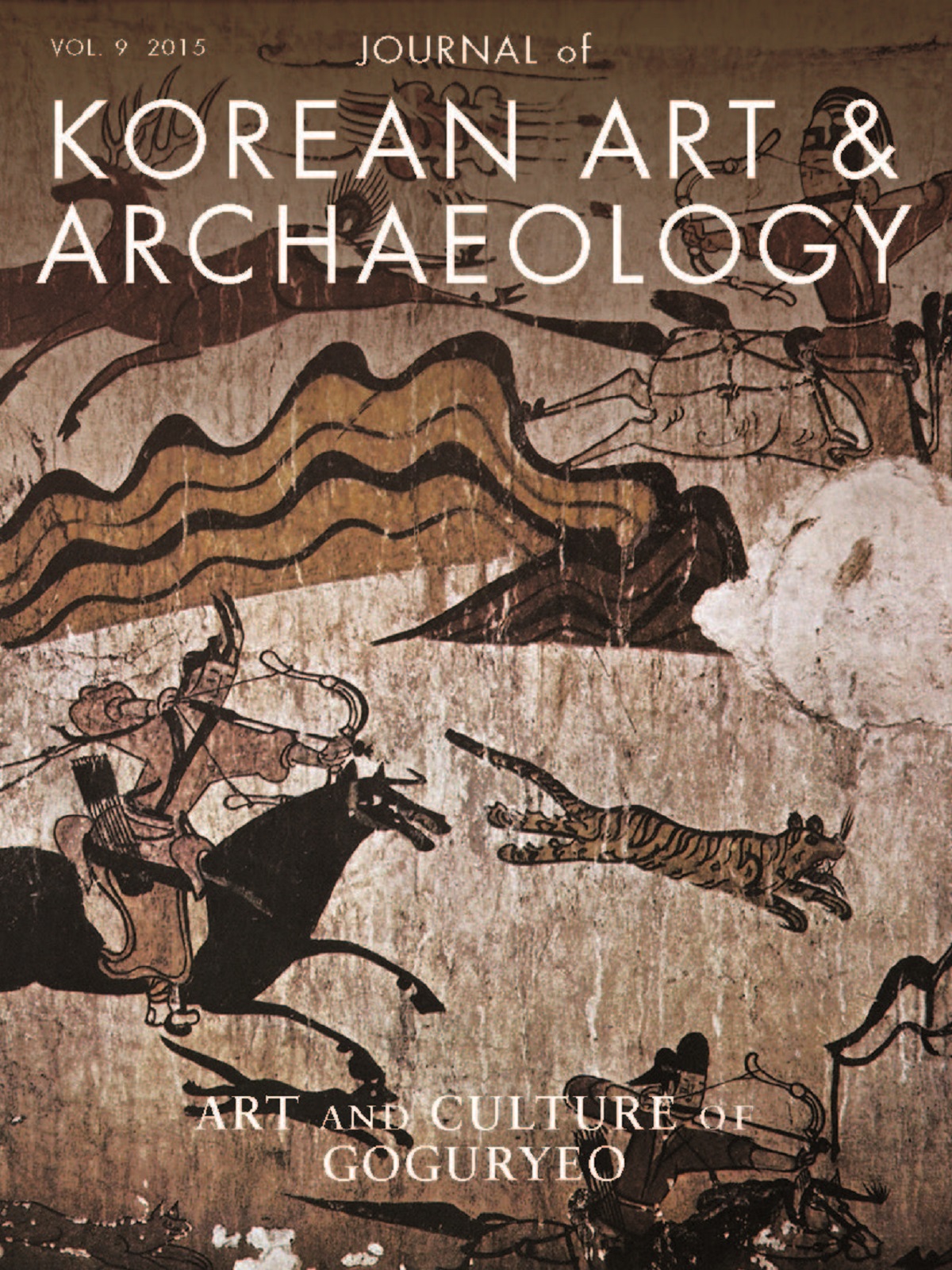

Journal of Korean Art & Archaeology 2015, Vol.9 pp.93-108

Copyright & License

The Buddhist pantheon includes deities like Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and arhats. Arhats are enlightened disciples of Buddha Shakyamuni who delay nirvana to protect Buddhist law. Often depicted as human monks in natural settings, arhat iconography is uncodified. In Korea, arhat paintings peaked during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties but are now scarce. A particular interest lies in the 16th-century LACMA Deoksewi painting, commissioned by Queen Munjeong, illustrating intricate court style and echoing Goryeo tradition. Munjeong's patronage reflects her devotion to Buddhism and arhat worship for ensuring the health and prosperity of the royal family amid challenges, thus demonstrating the interplay between spiritual and artistic traditions in Korea.

Introduction

The Buddhist pantheon comprises such deities as Buddhas, bodhisattvas, disciples, and guardians. Known as nahan in Korean and as luohan (羅漢) in Chinese, arhats (a Sanskrit name) are disciples of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni; they are human beings who have achieved enlightenment but have deferred entry into nirvana until the Buddha Maitreya finally appears. Possessing the supernatural powers of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, they remain on earth to protect the Buddhist law and to guide the spiritual progress of all sentient beings. They are worshiped as groups rather than as individuals; those groups sometimes include sixteen, sometimes eighteen, and other times even five hundred arhats.

Monks of the terrestrial realm, arhats differ from the divine beings confined to Buddhist ethereal or celestial planes. Arhat iconography is relatively uncodified, and paintings of arhats typically represent figures with naturalistic human features set in realistic environments. The need for paintings of arhats developed rapidly in China late in the Tang Dynasty (唐, 618 – 907) and Five Dynasties period (五代, 907 – 960) in accordance with the growth of arhat worship. Many paintings of arhats were produced in Korea during the Goryeo (高麗, 918 – 1392) and Joseon (朝鮮, 1392 – 1910) Dynasties; even so, most such paintings have disappeared due to wars or the internal circumstances of individual temples. In fact, only forty sets of Korean arhat paintings remain today, a number substantially lower than that of extant arhat paintings from China and Japan. Whatever the reason for this relative paucity, Korean arhat paintings have received but scant attention from scholars of East Asian Buddhist art. Even so, the few extant Korean paintings are representative of the period in which they were created and reflect a variety of iconographic types and painting styles. In this regard, they are crucial to understanding the development of the East Asian tradition of arhat painting.

The painting of Deoksewi, the 153rd of the 500 Arhats (第一百五三 德勢威尊者, hereafter “the LACMA Deoksewi”), in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) exemplifies the unique characteristics of Korean arhat paintings. Commissioned during the reign of King Myeongjong (明宗, r. 1545 – 1567) by his mother Queen Munjeong (文定王后, 1502 – 1565), a fervent Buddhist devotee, this painting reflects both the reverence for arhats during this period and the characteristics of court-sponsored Buddhist art. In addition, it is the only known arhat painting from the early Joseon period (1392 – 1592). First introduced by Kim Hongnam in 1991 (Kim Hongnam 1991, 40-41), this painting has been included in several studies, but most publications have provided only a short description of the iconography and the patron, leaving the scroll’s full importance yet to be explored. This paper will examine the LACMA Deoksewi painting’s composition and style as well as the circumstances of its patronage in order to reveal both its significance and the unique characteristics of Korean arhat paintings.

Queen Munjeong’s Arhat Worship

This Deoksewi scroll (Fig.1) measures 45.7cm in height and 28.9cm in width; it was painted in ink with highlights in vermillion, copper-green, dark blue, white, and gold pigments. The arhat is represented as a venerable old monk seated on a rock beneath a tree and holding a Buddhist sutra. The inscription at the upper right translates “The 153rd disciple Deoksewi” (第一百五三 德勢威尊者); an inscription along the painting’s left edge (Fig. 2) records:

In the fifth month of the imsul year (壬戌年, 1562), Great Queen Dowager Seongryol Inmyeong Daewang Daebi of the Yun clan had 200 arhat paintings created in honor of his majesty King Myeongjong and enshrined them at Hyangnimsa Temple on Mt. Samgak, for the King’s vitality, prosperous descendants, a flourishing nation, the welfare of the people, and her own longevity.

聖烈仁明大王大妃尹氏爲 主上殿下無病萬歲子盛孫興 國泰民安仰亦己身所願圓成壽星永曜 新畵成聖僧二百 幀掛安于三角山香林寺 聖烈仁明大王大妃尹氏爲 主上 殿下無病萬歲子盛孫興國泰民安仰亦己身所願圓成壽 星永曜 新畵成聖僧二百幀掛安于三角山香林寺

Fig. 1. Deoksewi. Joseon, 1562. Color on silk, 45.7 × 28.9cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Author’s photograph)

These inscriptions reveal that the painting was commissioned in 1562 by Queen Munjeong (referred to by the honorific title “Great Queen Dowager Seongryol Inmyeong Daewang Daebi”) as part of a commission for 200 arhat paintings for Hyangnimsa Temple (香林寺) on Mt. Samgak (三角山). The figure in the painting is clearly identified as Deoksewi, the 153rd disciple among the 500 arhats.

Queen Munjeong ruled as regent for her son King Myeongjong, the thirteenth Joseon monarch, who ascended the throne in 1545 at age twelve. She dominated the government during her eight-year regency and, even after retiring from this prominent role, continued to yield considerable political and governmental power. In contrast to other Joseon rulers who suppressed the public practice of Buddhism, she actively promoted Buddhist worship. Together with a prominent monk named Bou (普雨, 1515 – 1565), she restored the “Seunggwa jedo” (僧科制度, a royal court recruitment system for selecting Buddhist monks) and the “Docheop je” (度牒制, a royal court licensing system for Buddhist monks) that had been abolished during the reign of King Jungjong (中宗, r. 1506 – 1544). She also re-established the two major Buddhist sects, the Seon (禪宗, read Chan in Chinese, Zen in Japanese; training sect focused on meditation) and the Gyo (敎宗, read Jiao in Chinese; a sect focused on doctrinal study). In addition, Queen Munjeong significantly increased the number of naewondang (內願堂), or royal memorial shrines at which prayers could be offered for the repose of the souls of deceased members of the royal family and for their rebirth in the Western Paradise. According to the Myeongjong sillok (明宗實錄), approximately forty memorial shrines existed when Myeongjong ascended the throne in 1545, but by 1550, only five years later, seventy nine large temples had been newly designated as naewondang. The number of naewondang expanded to 400 in 1554, and by 1565, the twentieth year of King Myeongjong’s reign, nearly all temples in the kingdom had been registered as naewondang. Ministers of the royal court, who supported Confucianism as the state ideology, raised objections, however, and officials submitted numerous petitions to the king against the royal patronage of Buddhism and the expansion of the naewondang. Undeterred by these objections, Queen Munjeong continued her policy of reviving Buddhist worship. One way in which she demonstrated her commitment to the cause was by commissioning Buddhist paintings. In addition to the 200 arhat paintings produced for Hyangnimsa Temple, she commissioned more than 400 works, including the Bhaisajyaguru Mandala (1561) and Ksitigarbha and the Ten Kings of Hell (1562) as well as 100 paintings each of Shakyamuni Triad (1565), Amitabha Triad (1565), Bhaisajyaguru Triad (1565), and Maitreya Triad (1565) to commemorate the reconstruction of Hoeamsa Temple (檜巖寺).

Queen Munjeong was especially enthusiastic about arhat worship. As Buddhist disciples who have achieved enlightenment, arhats are believed to possess the power of both flight and physical transformation as well as the ability to extend their lifespans and to move the earth and the sky. Buddhist worshipers traditionally have beseeched arhats to intercede in periods of drought and national crisis and to answer prayers for earthly prosperity and good fortune. During China’s Five Dynasties period, for example, Buddhists prayed before the painting The Sixteen Arhats by Guan Xiu (貫休, 832 – 912) for relief from drought; such arhat worship continued into the Song Dynasty (宋, 960 – 1279). The Northern Song text Memoirs of Eminent Monks (高僧傳, 988) by Zan Ning (贊寧, 919 – 1001) includes many stories of arhats summoning their powers in response to prayers for rain. In Korea, Buddhist rituals related to arhats were widely performed during the Goryeo Dynasty, when the nation suffered from both foreign invasions and internal turmoil. Ordinary Koreans also prayed to arhats for health and longevity. It is not surprising, therefore, that painted representations of arhats reflect an association with prosperity and long life. For example, the arhats’ long beards and eyebrows symbolize their ability to extend their lifes-pans and to remain on Earth for long periods. It was this ability of the arhats, in particular, that underlay arhat worship in Korea in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Although the Joseon Dynasty maintained from its inception an official policy of promoting Confucianism and suppressing Buddhism among the general public, Buddhist worship continued within the royal court much as it had during the Goryeo Dynasty. At that time, the main reason for supporting Buddhist rituals at court was to pray for the safe passage of a deceased king into Paradise. Arhat worship on the other hand was characterized by an interest in achieving earthly prosperity and was particularly concerned with prayers for good health and long life. For example, the Taejong sillok (太宗實錄) describes how prayers were offered in a temple hall dedicated to arhats (羅漢殿, hereafter “arhat hall”) for Prince Seongnyeong (誠寧大君, 1405 – 1418) when he became critically ill. The Sejong sillok (世宗實錄) records that King Sejong (世宗, r. 1418 – 1450) ordered the performance of a ritual for arhat worship when the abdicated King Taejong (太宗, r. 1400 – 1418) fell ill. A passage in the second volume of Sigujip (拭疣集, Literary Collection of Sigu)—the collected writings of Kim Suon (金守溫, 1410 – 1481)—reveals that King Sejong’s wife, Queen Soheon (昭憲王后, 1395 – 1446), erected a hall for arhat worship at Wontongam Shrine (圓通菴) of Cheonggyesa Temple (淸溪寺) and installed stone sculptures of sixteen arhats as part of her appeals for the King’s longevity. A record of 1466 from the same Sigujip collection states that the monarch’s illness similarly prompted the Queen mother to construct an arhat hall at Sangwonsa Temple (上院寺) on Mt. Odae during the reign of King Sejo (世祖, r. 1455 – 1468).

This tradition of arhat worship continued during Queen Munjeong’s regency in the sixteenth century. In 1554, the Queen ordered the construction of an arhat hall at Jasugung (慈壽宮), a complex near the royal palace where the royal concubines of a recently deceased king resided and prayed for royal ancestors, and in 1562 she commissioned a set of 200 arhat paintings, including one representing Deoksewi, for Hyangnimsa Temple. The Na-am japjeo (懶庵雜著, Writings of Na-am) by Monk Bou states that the Queen commissioned a set of 500 paintings of arhats and ordered that the stone sculptures of sixteen arhats at Bongnyeongsa Temple (福靈寺) be moved to Bongeunsa Temple (奉恩寺) for repair

Queen Munjeong’s reverence for arhats appears to have been closely related to the precarious situation of the royal family at that time. During Myeongjong’s reign, the King, his mother (Queen Munjeong), and his only son, all suffered ill health. The King found himself in a perpetual state of worry about his mother and her family, many members of which continued to involve themselves in political affairs even after Queen Munjeong’s eight-year regency ended in 1553, as well as about government officials who fiercely resisted their influence. Whether or not it was because of such constant stress, King Myeongjong struggled with chronic illness. Furthermore, the King and his Queen and six Royal Concubines produced only a single heir, Crown Prince Sunhoe (順懷世子, 1551 – 1563), and this sickly child died in 1563, just a year after the production of the arhat paintings for Hyangnimsa Temple in 1562. It seems that Queen Munjeong also was not in good health during the time when she was actively promoting arhat worship, as she passed away only three years after the Hyangnimsa Temple commission. The Queen’s own motivation for producing the Deoksewi painting supports this interpretation. As previously mentioned, the inscription reads: “Great Queen Dowager Seongryol Inmyeong Daewang Daebi of the Yun clan produced 200 arhat paintings in honor of his majesty King Myeongjong and enshrined them at Hyangnimsa Temple on Mt. Samgak, for the King’s vitality, prosperous descendants, a flourishing nation, the welfare of the people, and her own longevity.” This inscription strongly suggests that the Queen hoped to overcome the perilous difficulties of the royal family through an appeal to the Buddha for mercy and through her profound commitment to arhat worship.

The Deoksewi scroll and the other works from the same commission were housed at Hyangnimsa Temple on Mt. Samgak in the vicinity of the royal palace. During the Khitan (契丹) invasions, which occurred during the reign of the Goryeo King Hyeonjong (顯宗, r. 1009 – 1031), this temple also housed the coffin of the Goryeo founder, King Taejo (太祖, r. 918 – 943). Extant records from the Goryeo period include no detailed mention of this, but records concerning Hyangnimsa Temple and the Goryeo royal family do appear in such Joseon texts as the 49th volume of the Sukjong sillok (肅宗實錄) and the Sinjeung dongguk yeoji seungnam (新增東國輿地勝覽, New Augmented Survey of the Geography of Korea; 1530). These sources indicate that Hyangnimsa Temple maintained an especially intimate connection with the royal family from as early as the Goryeo period. Unfortunately, only the temple site remains today, so it is virtually impossible to establish the location and exact dimensions of the building where the arhat paintings were enshrined. Although it is not possible to know how the 200 paintings were displayed in the temple hall, there are clues that help us to understand how these works functioned.

Arhat paintings are now appreciated as works of art; on a functional level, however, they belong to the category of religious paintings commissioned for the purpose of worship and the accrual of “merit” (功德), or meritorious karma. Like most other Buddhist works of art, arhat paintings were enshrined inside a temple hall and were used during worship. In the late Joseon period, for example, arhats were represented in the wall paintings of an arhat hall or of the main hall (大雄殿) of a temple, just as they were also depicted in hanging scrolls that were also displayed in those halls. However, the 200 arhat paintings produced for Hyangnimsa Temple, including the LACMA Deoksewi, likely were produced for rituals honoring arhats and donated as a means of accruing merit, or meritorious karma, rather than to serve as the focus of worship in a temple hall, as evinced by their relatively small size (viz. only 45.7cm in height and 28.9 cm in width). By contrast, scrolls intended to serve as the focus of worship generally were larger in order to create a more striking visual impact.

The works Queen Munjeong commissioned for the purpose of ritual also support this assumption. In 1565, the Queen sponsored the production of 400 paintings of approximately the same size (100 paintings representing each of Shakyamuni, Bhaisajyaguru, Amitabha, and Maitreya) (Fig.3). An inscription in gold at the bottom of each painting details the reason for the commission and the intended function of the paintings. According to these texts, the 400 paintings were produced for the vitality of the king and the prosperity of royal descendants. The commission coincided in time with a ceremony celebrating the restoration of Hoeamsa Temple. After the completion of the ceremony, the paintings were to be dispersed throughout the country and enshrined in various temples.

Fig. 3. Bhaisajyaguru Buddha Triad. Joseon, 1565. Gold on red silk, 58.7 × 30.8cm. Paintings of the Joseon Dynasty (韓國·朝鮮の繪畵) (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2008, p. 105)

Therefore, it seems unlikely that the 200 arhat paintings produced for Hyangnimsa Temple were installed in temple halls for the purpose of worship. Rather, it is much more likely that they were intended to honor various arhats for ritual purposes as part of an effort to accrue merit through the performance of good deeds and to ensure the long life of the King and the prosperity of his descendants.

The Legacy of Goryeo Arhat Iconography

Buddhist paintings are generally based on a particular sutra text. For example, paintings of the preaching Shakyamuni Buddha are based on a section from the Lotus Sutra (妙法蓮華經, Saddharmapundarika Sutra). Paintings of Amitabha Buddha draw from the Three Pure Land Sutras (淨土三部經): The Infinite Life Sutra (大無量壽經, The Larger Sukhavativyuha Sutra), Contemplation Sutra (佛說觀無量壽佛經, Amitayurdhyana Sutra), and Amitabha Sutra (阿彌陀經, The Smaller Sukhavativyuha Sutra). Paintings of the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara refer to the “Chapter on the Entry into the Realm of Reality” (入法界品) in the Flower Garland Sutra (華嚴經, Avatamsaka Sutra) or the “Chapter on the Universal Gate of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva” (觀世音菩薩普門品) in the Lotus Sutra. The precise subject of these paintings and their representation are based on the corresponding textual sources. The iconography of arhat paintings, by contrast, does not derive from a single textual source, despite a partial reflection of the character and descriptions taken from such texts as the Nandimitravadana (佛說大阿羅漢難提密多羅所說法住記, A Record of the Perpetuity of the Dharma Narrated by the Great Arhat Nandimitra). In general, the image of a Buddhist monk served as the prototype for the representation of arhats. Lacking a predetermined or set iconography for each arhat, painters were permitted a great deal of artistic license in the expression of each arhat’s particular appearance and individual spiritual powers. In some instances, painters used the same iconographic type to describe all the arhats. An image of the seventeenth arhat “Samghanandi” (僧迦難提尊者) (Fig. 4) from the Ming-Dynasty (明, 1368 – 1644) encyclopedia Sancai Tuhui (三才圖會, Illustrations of the Three Powers), for example, depicts a figure seated in contemplation near a body of water. This image served as the basis for the fifteenth arhat “Ajita” (阿氏多尊者) (Fig. 5) in the set of sixteen arhat paintings at Heungguksa Temple (興國寺), Yeosu, and also for the twelfth arhat “Nagasena” (那伽犀那尊者) (Fig. 6) in another set of sixteen arhat paintings at Songgwangsa Temple (松廣寺), Suncheon. In addition, the iconography of an arhat cloaked in a robe that covers the top of his head and extends downward to his feet, a symbol of his enlightened state, is usually understood as a reference to the monk Bodhidharma (達磨, fifth or sixth century). However, this iconographic type had already evolved in China’s Northern Wei (北魏, 386 – 535) period, before arhat paintings became popular, and it also appears in paintings that portray the sixteen arhats but do not include Bodhidharma.

Fig. 4. Samghanandi, 17th of the 500 Arhats, from Sancai Tuhui. Woodcut. Ming Dynasty, 1609. Dongguk University (Author’s photograph)

Fig. 5. Ajita, 15th of the Sixteen Arhats, from a set of the sixteen arhat paintings. Color on hemp cloth. Joseon, 1723. Heungguksa Temple, Yeosu (Author’s photograph)

Fig. 6. Nagasena, 12th of the Sixteen Arhats, from a set of the sixteen arhat paintings. Color on hemp. Joseon, 1725. Songgwangsa Temple, Suncheon (Author’s photograph)

The LACMA Deoksewi follows the typical presentation of an arhat in paintings: a male figure dressed in long monk’s robes, set before a nimbus, and seated on a rock beneath a pine tree, his body turned slightly to his right, and his hands holding a sutra from which he reads. It is probable that the artist arbitrarily selected this image from among a great variety of different iconographic forms and then, in the painting’s inscription, arbitrarily identified the arhat as the 153rd disciple. It was customary to produce sets of 500 paintings, each painting representing one of the 500 arhats. However, the inscription on the Deoksewi scroll indicates that only 200 paintings were produced and given to Hyangnimsa Temple. It is unclear whether the original commission was for just 200 paintings or was for 500 paintings, with 200 to be enshrined at Hyangnimsa Temple and the remaining 300 at a separate temple (or temples). This matter necessarily will remain unclear until more data come to light.

The artist of the LACMA Deoksewi expertly focuses attention on the individual arhat, omitting additional figures that could detract from the main figure. One of the oldest employed in arhat paintings, this composition can be found in such early Chinese paintings as Guan Xiu’s The Sixteen Arhats. A set of Goryeo-period paintings representing the 500 arhats (hereafter “The 500 Arhats from the Goryeo period”), which are produced in 1235 and 1236 according to the inscriptions on the paintings, also follows this compositional organization (Shin Kwanghee 2012). Measuring 55 cm in height and 40 cm in width, each of the 500 paintings depicts a single arhat who is identified by an inscription near the top of the painting. Each painting’s composition is extremely simple, with most figures cloaked in monk’s robes, perched atop a rock, and backed by a nimbus, the figures sometimes holding a few objects, likely ritual offerings. These paintings are closely related to the LACMA Deoksewi in terms of size and composition. Other extant arhat paintings from the Goryeo period include those featuring a group of arhats in a single composition, as exemplified by The 500 Arhats in Chion-in (知恩院), Kyoto, and the Shakyamuni Triad with the Sixteen Arhats in the Nezu Museum (根津美術館), Tokyo (Sigongsa 1996; National Museum of Korea 2010). However, the LACMA Deoksewi is closer in style and composition to The 500 Arhats from the Goryeo period. Among these 500 works, elements in Bosu, 282nd of the 500 Arhats (Fig. 7) closely resemble related elements in the LACMA Deoksewi. In each work, the figure is seated, appears under a branch, turns slightly to his right, and holds a sutra.

Fig. 7. Bosu, 282nd of the 500 Arhats. Goryeo, 1236. Ink and color on silk, 54.6 × 31.7cm. Kyushu National Museum (Author’s photograph)

Other early Joseon-period arhat paintings too draw on Goryeo iconographic and compositional types. Sketch of an Arhat (Fig. 8) by Yi Sangjwa (李上佐) in the collection of the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, falls into this category. In this simple sketch, the arhat is presented in the guise of a monk wearing a full-length robe and holding an alms bowl in one hand and a ruyi (如意) scepter in the other; a small, hand-held censer also appears in the sketch. The figure appears to be attempting to lure a dragon into the alms bowl. Similar to the LACMA Deoksewi and The 500 Arhats from the Goryeo period, this sketch—perhaps an unfinished work, perhaps a preliminary draft for a painting—depicts a single arhat without accompanying figures. The motif of luring a dragon into an alms bowl, in particular, closely resembles the subject of Segongyang, 464th of the 500 Arhats (Fig. 9) from The 500 Arhats from the Goryeo period.

Fig. 8. Yi Sangjwa, Sketch of an Arhat. Joseon, mid-16th century. Ink on paper. 41.0 × 23.7cm. Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art. National Treasures from the Early Joseon Period (조선전기국보전) (Seoul: Hoam Museum of Art, 1996, Fig. 199)

Fig. 9. Segongyang, 464th of the 500 Arhats. Goryeo, 1235–6. Ink and color on silk, 52.8 × 40.8cm. Cleveland Museum of Art, USA. Buddhist Paintings of the Goryeo Dynasty (고려시대의 불화) (Seoul: Sigongsa, 1997, Fig. 128)

That the LACMA Deoksewi follows the Goryeo tradition of the 500 arhats paintings is further supported by the nomenclature used in the inscription of the LACMA Deoksewi. Today, two systems exist in East Asia for identifying the 500 arhats. The system used in China and Japan is based on the Southern Song-Dynasty stele Luohan zunhaobei (羅漢尊號碑, stele of the names of arhats), which once was housed in Qianmingyuan (乾明院), Zhejiang Province. A second system has been used exclusively in Korea since Goryeo times. The Luohan zunhaobei identifies all the disciples of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni listed in the sutras as well as the line of Chinese successors. It even includes eminent Korean monks from the Silla period (新羅, 57 BCE – 935). The actual names of the Buddha’s disciples mentioned in the sutras, such as “Ajnatakaundinya” (阿若憍陳如) and “Aniruddha” (阿尼樓), are listed first in the genealogy. As the list continues, however, the Luohan zunhaobei shows more conceptual names that are explicitly derived from Buddhist principles, such as “Vajra Radiance” (金剛明), “Freedom from Attachment” (無愛行), and “Remains in the World” (住世間). Such conceptual names derived from Buddhist principles predominate in the Korean nomenclature of arhats, as the list begins with the first arhat “Dharma Sea” (法海), the second “Lightening Flash” (電光), and continues featuring such doctrinal names up until the 500th arhat “Immeasurable Meanings” (無量義). The actual names of Buddha’s disciples are rarely mentioned in the Korean list; as a consequence, the Chinese/Japanese and Korean designations share only three or four names in common for the 500 arhats. Chinese, Koreans, and Japanese use the same system of names for the group of sixteen arhats, a system derived from the Nandimitravadana; however, no sutra identifies all the arhats in the group of 500. Obviously, different name designations have been adopted in China and Korea as the genealogical systems evolved (Shin Kwanghee 2010, 28-43).

The inscription on each of the paintings in The 500 Arhats from the Goryeo Dynasty evinces the development of a separate arhat genealogy in Korea. Even so, it is difficult to interpret the complete picture because only fourteen paintings are known to remain from the original set. Though later in date, Obaekseongjung cheongmun (五百聖衆請文, Invocation of the Five Hundred Arhats; 1805) (Fig. 10) from the Geojoam Monastery (居祖庵) provides the Korean designations of the 500 arhats as well as insight into the date those names were established. The book follows the form of an invocation (奉請) and records the names of all 500 arhats. In the preface, the author states that both the ritual associated with the 500 arhats and the systematization of arhat genealogy were based on a text on related rituals written by Monk Muhak (無學, 1327 – 1405) at Seogwangsa Temple (釋王寺) late in in the Goryeo Dynasty. Accordingly, the Korean system of arhat genealogy dates back at least to the late Goryeo period. The names recorded on the fourteen extant arhat paintings from the Goryeo period further corroborate the genealogy outlined in the Obaekseongjung cheongmun, which indicates that this nomenclature extends back as far as to 1235 – 36 when the fourteen works were produced. For example, the 282nd arhat is recorded as “Bosu” (寶手) meaning “Precious Hand” in both the corresponding painting from The 500 Arhats from the Goryeo period and the Obaekseongjung cheongmun. The 153rd arhat likewise is recorded as “Deoksewi” in both the LACMA painting and the Obaekseongjung cheongmun (Figs. 11 and 12).

Fig. 10. Obaekseongjung cheongmun. Joseon, 1805. 44.0 × 32.5cm. Eunhaesa Museum (Author’s photograph)

These observations show that the LACMA Deoksewi inherited its composition, iconography, nomenclature, and other elements from the set of 500 arhats from the Goryeo period. It also demonstrates how arhat iconography from the Goryeo Dynasty formed the basic communicative mode for the 200 arhat paintings commissioned by Queen Munjeong for Hyangnimsa Temple.

Development and Spread of Court Style of Buddhist Paintings

The LACMA Deoksewi presents an exceptionally realistic description of an arhat as a venerable old monk. The white hair, eyebrows, beard, and ear-hair are painted in meticulous detail (Fig. 13). Cloud patterns, small chrysanthemum florets, and vajra thunderbolts (金剛杵), all painted in gold, embellish his robe (Fig. 14). Painted in black ink, a rock and a pine tree provide a setting for the figure. The rock, whose unembellished top suggests a flat surface on which the arhat can sit, boasts bold outlines that reveal both the artist’s dexterity with brush and ink and the influence of China’s “Zhe school” (浙派) on his painting style (Fig. 15). Extant landscape paintings with figures from the first half of the Joseon period rarely include a precise date; by contrast, this arhat painting can be definitively dated to 1562. Therefore, the LACMA Deoksewi holds special significance for research both on Buddhist painting and on the development of the Zhe-school style in secular works of art from that time.

Because the painting lacks a signature, it is virtually impossible to identify the artist who painted the LACMA Deoksewi. (In fact, most court-sponsored Buddhist works of art from the early Joseon period also lack artists’ signatures). Given that the painting’s patron, Queen Munjeong, was the most powerful figure of that era, and given that the painting boasts a stable composition, elegant brushwork, and skillful application of color, a court painter of exceptional skill likely created this work. Because this painting is similar in style to other Buddhist paintings commissioned by the royal family during the reign of King Myeongjong, it is possible that the same artist, or group of artists, was involved in the production of all of these works. The depiction of the arhat’s face and the patterning on his robe, for example, closely resemble the description of the face and clothing of the Buddha’s disciples in Gathering of the Four Buddhas (1562) (Fig. 16), a painting produced in exactly the same year for Yi Jongrin (李宗麟, 1536 – 1611), a member of the Yi royal family, who used the sobriquet “Pungsanjeong” (豊山正). The rock, moss, and pine tree in the LACMA Deoksewi also bear striking similarity to the rocks and tree branches in Thirty-two Responsive Manifestation of Avalokitesvara (Fig. 17), a painting produced in 1550 for Queen Gongui (恭懿王大妃, 1514 – 1577), the consort of King Injong (仁宗, r. 1544 – 1545).

Fig. 16. Gathering of the Four Buddhas, detail. Joseon, 1562. Color on silk, 90.5 x 74.0cm. National Museum of Korea. Buddhist Painting of Korea vol. 39 (한국의 불화 39) (Seoul: Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage, 2007, p. 64)

Fig. 17. Thirty-two Responsive Manifestation of Avalokitesvara, detail. Joseon, 1550. Color on silk, 201.6 × 151.8cm. Chion-in, Japan. Paintings of the Joseon Dynasty and Japan (朝鮮王朝の繪畵と日本) (Osaka: Yomiuri Shimbun, 2008, Fig. 101)

The appearance of Buddhist paintings from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries varies according to the status of the patron, the basic polarities basically being royal patronage and popular patronage. Royal patronage refers to works produced for the Queen or the royal concubines, princes, other members of the royal family and their associates; popular patronage refers to works of art sponsored by regular officials or even people belonging to the secondary class of jungin (中人), or middle-level people. Paintings done under royal patronage follow the court style and set the standard for Buddhist painting of the era. Executed by the best painters of the day, court-style Buddhist paintings reflect exceptional artistic accomplishment in their elaborate compositions, refined depictions of landscapes, and clear focus on the subject. In particular, they typically sport a large amount of gold pigment. Two prominent examples are Sixteen Visions of the Contemplation Sutra, commissioned in 1465 by Prince Hyoryeong (孝寧大君, 1396 – 1486), the second son of King Taejong and the brother of King Sejong, and Ksitigarbha and the Ten Kings of the 18 Hells, produced between 1575 and 1577 for King Myeongjong’s royal concubine Sukbin of the Yun family (淑嬪 尹氏). Both paintings include a variety of motifs; the Sixteen Visions painting clearly delineates the “sixteen meditations” (十六觀) outlined in the Contemplation Sutra, while the Ksitigarbha painting features scenes of the underworld (冥府) with related religious icons, based on such Buddhist texts as the Ksitigarbha Sutra (地裝菩薩本願經). In the Thirty-two Responsive Manifestation of Avalokitesvara, which was produced for King Injong’s consort, the artist showcased his very accomplished talent by filling the entire composition with landscape elements. These court-style paintings are valued both for their outstanding artistic merit and for their extensive use of gold pigment, especially in the patterns on the figures’ clothing.

The LACMA Deoksewi reflects many of these characteristics of court-style Buddhist painting from the early Joseon period. The artist highlights the arhat motif, embellishing his robe with beautiful patterns in gold, and embraces an energetic expression of the landscape with well-balanced composition and detailed brushwork, resulting in a very highly finished appearance. The artist must have possessed considerable understanding of the tradition of representing arhats. Compared to paintings of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, paintings of arhats typically feature extensive use of ink and a highly detailed, naturalistic description of facial features. The LACMA Deoksewi follows that tradition, particularly in the application of ink; compared to the Goryeo example (Fig. 9), however, the figure is more slender and elongated. In addition, the gold patterns appear over the entire robe, but in the Goryeo example the patterns appear mainly on the edges of the robes. In that context, the LACMA Deoksewi follows the basic style of arhat painting established in the Goryeo period but also incorporates intricate details, a characteristic of the Joseon courtpainting style. Although it shares stylistic elements with contemporary court-sponsored Buddhist paintings, it nevertheless retains characteristics that are particular to the specific genre of arhat painting.

The court-style of depicting arhats, as revealed by the LACMA Deoksewi, inspired arhat paintings done by temple monks under popular patronage. No early Joseon paintings of individual arhats done under popular patronage remain today, so none can be directly compared to the LACMA Deoksewi. Even so, many Buddhist paintings done under popular patronage and featuring the sixteen arhats or the ten disciples survive; in those paintings the figures are portrayed in a manner similar to the arhats in court-style Buddhist paintings, including the LACMA Deoksewi. For example, the face of the old monk known as Mahakasyapa (摩訶迦葉尊者) in the late sixteenth-century painting Preaching Shakyamuni Buddha—in the collection of Kōshō-ji Temple (興正寺), Kyoto, Japan—closely resembles the description of the arhat in the LACMA painting. The facial wrinkles, the eyebrows, and the manner in which the artist depicted the figure’s beard are similar in both works. Arhats and monks represented in other contemporary paintings, such as Preaching Shakyamuni Buddha (1569) in the old collection of Hōkō-ji Temple (寶光寺), Kameoka, Kyoto Prefecture, Japan, and Nectar Ritual (1580) in a private Korean collection, also share similarities with the arhat in the LACMA scroll in terms of the shape of the faces, long eyebrows, and other physical features.

The LACMA Deoksewi, the only remaining arhat painting from Queen Munjeong’s commission, illustrates the court-style of Buddhist painting from the sixteenth-century, just as it also demonstrates how the court style stood as a stylistic model for Buddhist paintings done under popular patronage.

Conclusion

The LACMA Deoksewi is one of the 200 paintings of arhats produced for Hyangnimsa Temple in 1562, a set commissioned by Queen Munjeong in supplication for the health and longevity of her son, King Myeongjong, and to ensure a line of prosperous descendants. Queen Munjeong played a key role in reviving Buddhism in the sixteenth century and enthusiastically engaged in arhat worship as part of her sponsorship of services at Buddhist temples. Arhats are spiritual beings that possess divine power to extend lifespans and reward worshippers with both good fortune and long life in the terrestrial world. Queen Munjeong appealed to these beings for the welfare of her son, King Myeongjong, and her grandson, both of whom suffered from illness, and for her own wellbeing as she approached old age. The LACMA painting focuses on the figure of Deoksewi, the 153rd of the 500 arhats, and presents him seated on a rock and reading a Buddhist sutra, without any attendant figures. Only the inscription in the upper right corner of the painting indicates his identity. Both the composition and the iconography indicate that the set of arhat paintings commissioned by Queen Munjeong closely followed the Goryeo tradition, as evinced by the set of 500 Arhats from the Goryeo period. It is also important that the name of the arhat, as recorded in the inscription, corresponds to an independent arhat genealogy developed in Korea. Representative of the sixteenth-century court-painting style, the painting is notable for its artistic sophistication. The artist’s skill is evident in the stable composition, delicate lines, and exceptionally forceful brushstrokes; the subtle description of the arhat’s expression imparts spiritual force.

The LACMA Deoksewi painting provides a window onto both the spiritual beliefs of Queen Munjeong, the Joseon royal court’s most representative Buddhist practitioner and sponsor of Buddhism, and the style, iconography, and function of arhat paintings of that era. It also reveals the unique characteristics that distinguish Joseon arhat paintings from contemporaneous Chinese and Japanese paintings of arhats.

- 987Download

- 3229Viewed

Other articles from this issue

- Editorial Note

- Development of Goguryeo Tomb Murals

- The Structure and Characteristics of Goguryeo Fortresses in South Korea

- Origins of Early Goguryeo Stone-piled Tombs and the Formation of a Proto-Goguryeo Society

- The Murals of Takamatsuzuka and Kitora Tombs in Japan and Their Relationship to Goguryeo Culture

- The Material Culture of the Royal City Identified in the Peripheral Regions of Baekje

- Buddhist Paintings and Suryukjae, the Buddhist Ritual for Deliverance of Creatures of Water and Land